All About Mate — Argentina's National Drink

Mate, yerba, termo. These three words are an irreplaceable part of nearly every Argentinian's life, and you do not have to do more than step outside in Argentina to see someone drinking it, their ‘termo’ (thermos) clutched under their arm.

Before I arrived in Buenos Aires to start my year abroad, I had never even heard of this drink. Within one week of arriving, I was seeing it everywhere, even considering buying my very own mate cup (I did so one month later), and being offered it by my classmates. Come 6pm in most city parks, you would see people gathering to share mate together, perhaps with some biscuits or other snacks to accompany. This cultural ritual is hugely popular in Argentina, but what many don't know is that is has a rich history which dates to pre-colonial times.

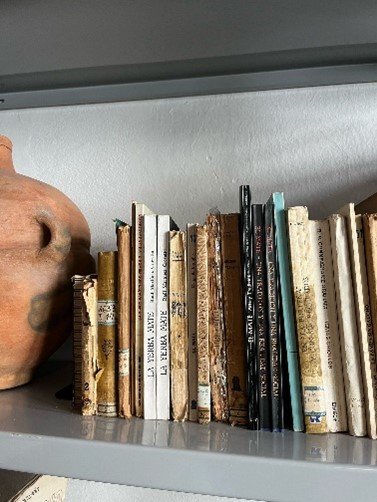

A whole section on books about mate in the Museo de Arte Popular José Hernández, Buenos Aires — Image belongs to author.

The history — from Guaraníes to Jesuits

The yerba mate plant’s scientific name is Ilex paraguariensis, and it grows in the north of Argentina, Paraguay, and south of Brazil. Its use dates to pre-conquest times, with Guaraní indigenous people (mostly in modern-day Paraguay) using the leaves as an infusion, object of worship, and even currency to barter with other villages. However, it was consumed differently to nowadays: they chewed the leaves or drank it in an infusion with cold or lukewarm water. They also only drank it once a day, as opposed to the very regular consumption of many Argentinians (1).

From the moment of the conquest, mate’s history becomes entangled with that of the Spanish conquistadores and then the Jesuits. Settlers noticed that the Guaraní people drank mate as an infusion for its energizing and healing properties and so adopted the practice. Jesuits then changed the growing techniques and started mass-producing it as an export economy (2) It became a trading commodity and was diffused throughout the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata (roughly modern-day Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay). Over time, they also changed the way of drinking it to more closely resemble modern day use, by adding hot water and a straw. Since then, the tradition has remained mostly unchanged, and according to the ministry of Culture of Argentina, around 100 litres of mate are consumed per person per year. The mate yerba itself is sold as a dark green leafy herb. Supermarkets have entire aisles devoted to different mate brands, with different people swearing by different brands and blends.

A supermarket selection of mate — Image belongs to author.

How to drink like a local

Once you have navigated the supermarket shelves (do I want bitter or sweet? Is 5mil pesos too much for yerba?) you put the herb (yerba) in your cylindrical cup.

You put the yerba in at a tilt until the cup is ¾ full, and place the straw (bombilla) in it. Then, pour hot but not boiling water in. Fun fact: Argentine kettles have a mate setting to get your water to the perfect temperature.

If having mate with others, the person who serves the mate drinks first. They drink, then pass it to others in an order after each refill. The same person always refills with water and passes. Everyone drinks from the same straw and the same cup (I was informed that the COVID-19 pandemic was a nightmare in this regard). It is very social, and Argentines are very generous; I first drank it with Argentine classmates who did not even know me. Once you’ve navigated those steps, there’s the taste. At first, many people do not like it; the drink starts off tasting like a bitter green tea or matcha. The more people it is passed around to, the less bitter it becomes, but in no way is it sweet. I also did not initially love it, but it grew on me over time, as did my appreciation for the social ritual that it is.

Sharing mate whilst marching in a university protest — Image belongs to author.

Mate etiquette:

Once placed in the cup, do not move the straw – unless you want to anger any Argentinian around you. This is to prevent herbs entering when you drink it, because the straw has a filter.

Do not wet all the yerba at once – leave some dry to maintain a stronger taste in later refills.

Drink all of the water in your fill but do not slurp it

Do not say thank you when you receive the mate cup. Saying gracias means you are done and don’t want anymore. This certainly went against my British politeness cues at first!

To conclude, I will always remember the culture of mate as a big part of my year abroad experience in Buenos Aires. It is hard not to, when mate is regularly drunk in more than 90% of Argentinian homes. It really is a cultural symbol of the country, across differing ages and classes. It has been interesting in this article to dive into the history behind the lived reality, and to see how the drink has been present throughout different regimes and political systems. What remains to be seen, however, is if mate will ever reach such popularity on this side of the ocean.

Handmade mate cups for sale in a market — Image belongs to author.

References:

(1) Alonso de la Madrid to Governor Hernandarias, Asuncion, 10 February 1596, cited by Aguirre, Diario, 2: pt. 2, p. 359

(2) López, Adalberto. “The Economics of Yerba Mate in Seventeenth-Century South America.” Agricultural History, vol. 48, no. 4, 1974, pp. 493–509. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3741386