A Long, Long Time Ago, a Book you Read Changed your Life

By Lizzy Riley

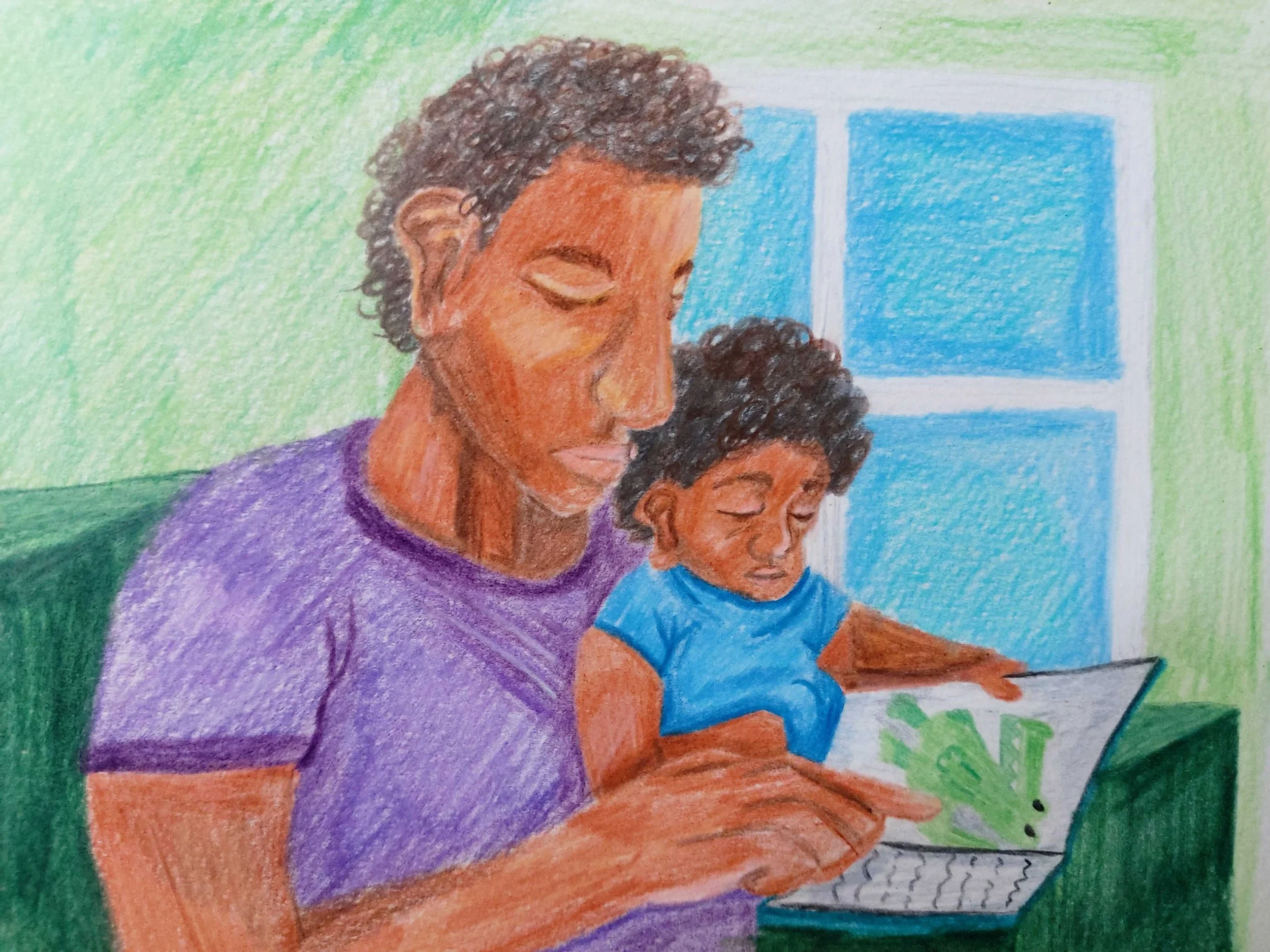

Image credit: Will Anderton-Pithers

When I was little, my favourite book was 'The Bad-Tempered Ladybird' by Eric Carle. My dad would rest me on his knee and recite the story of a very angry ladybird, who, in his version, was an extremely aggressive Brummie (an impressive feat for a born and bred Scouser). Soon enough, I was able to follow along with the story and even at age three I knew it almost by heart. There were lots of books like that; I knew that a mouse took a stroll through the deep dark wood and that Charlie's little sister was small and very funny. Even all these years later, bedtime stories hold a special place in my heart, and I like to think that they have only ever had a positive impact on my life. Having said this, I still think all insects sound like Ozzy Osbourne.

But beyond this odd Black Sabbath creepy crawly crossover, the picture books I read as a child left their mark on me in another way: my language. Obviously, books are good for language learning (we’ve all had English teachers ram that fact down our throat) but why is this?

Well, first we have to look at the content of the books, specifically the words. You’d be surprised at how advanced some of the vocabulary is in these little stories. Take ‘The Gruffalo’ for example: long words with complex spelling such as ‘poisonous’ and ‘underground’ are liberally thrown in by Julia Donaldson to be ingested by three-year-olds. Surprisingly though, this isn’t a huge issue. Picture books are the starting point for many children’s exposure to new language which they then start to use every day. Coupled with familiar sentence structures, children are able to better understand the role that certain words play and how they can relate to the vocabulary that they already know. The same can be said for the inverse, with the definition of a familiar word helping the child to decode the rest of the sentence.

So, unsurprisingly, a big win for the vocab side of things. But how many toddlers do you know that are able to read whole books alone, apart from Matilda Wormwood? Ninety-nine percent of the time, there’s an adult or older child reading with them. And so, a conversation is had. It’s a known fact that children ask questions a gazillion times a minute and this is multiplied by four when a book is involved. This usually comes with the nicknamed ‘imaginary’ topics of the books. We’re talking dinosaurs, we’re talking spaceships, we’re talking cats who turn up and wreck your house only to completely refurbish it before your mum returns. The strangeness and excitement of the topic of picture books combined with every child’s inquisitive nature provide for unique conversation. Chats like these are vital in Jerome Bruner’s Input theory of language acquisition. Bruner believed that interaction with more knowledgeable others (or MKOs) is what sparks a child’s ability to learn language. Every time a question is asked, the rules and processes that come with communication are explored and thus, understood.

Obviously, we need to look at the concept and nature of the books themselves, too. One key feature can be found in the name: picture books. From the age of one to about six, children are in what is known as the iconic stage - when pictures or ‘icons’ play a major role in a child’s cognitive development. The illustrations of pirates sailing the seven seas and princesses locked in towers give the child a visual representation of the words they’re hearing, causing their tiny brains to make lightning-fast connections between them. This also applies to the other senses. I don’t know the last time you were in the children’s section of a Waterstones (I visit it regularly simply for the nostalgia), but you’ll often find sensory books with different textures, and this has the same effect on vocabulary as pictures.

Another hallmark of children’s books is the inclusion of repetition, rhyme, and repetition. Many stories have recurrent phrases which a child can join in with (think: ‘We’re going on a bear hunt’) and through this they become more familiar with syntax and definitions. The addition of a steady rhythm can aid the identification of specific grammatical structures and children can work out how to manipulate language for their own purposes, as suggested by researcher Paul Ibbotson. He stated that children look for patterns and view sentences in chunks to be separated. So, in the instance of Michael Rosen, ‘we’re going on a’ and ‘bear hunt’ are two different phrases with different informative purposes.

The final chapter in this linguistic story is the future benefit of reading these books on a child. At their core, books are meant to be fun. What they are about doesn’t matter, it’s whether they’re enjoyable for the child to read. The book might be about a time travelling dolphin from Jupiter but if the dolphin spends the entire story filling out their tax returns the child will hate it. The entertainment that comes from picture books creates a mental link between learning and fun which creates an autonomous learner in time for the child to start school.

And there you have it. Story books truly are magical things and not just because they’re full of wizards and fairies. Each and every aspect of them can do a world of good for the language of children, or at least their understanding of it. So, the next time you see a toddler with a copy of Where the Wild Things Are, just know that they’re reading happily forever after. The End.