duck autocorrect!!

Alexander Shtyrov

“…an incredibly annoying spinning circle on the bottom right of the Google Doc…”

I recently downloaded Grammarly and Grammarly, in return, paid me a compliment. According to the “AI-powered writing assistant”, my writing is top-notch: unbelievably clear, very engaging, and exquisitely delivered. I have never considered my essays to be paragons of engaging writing, but it turns out that they are in less need of the Grammarly treatment than perhaps pieces by established authors.

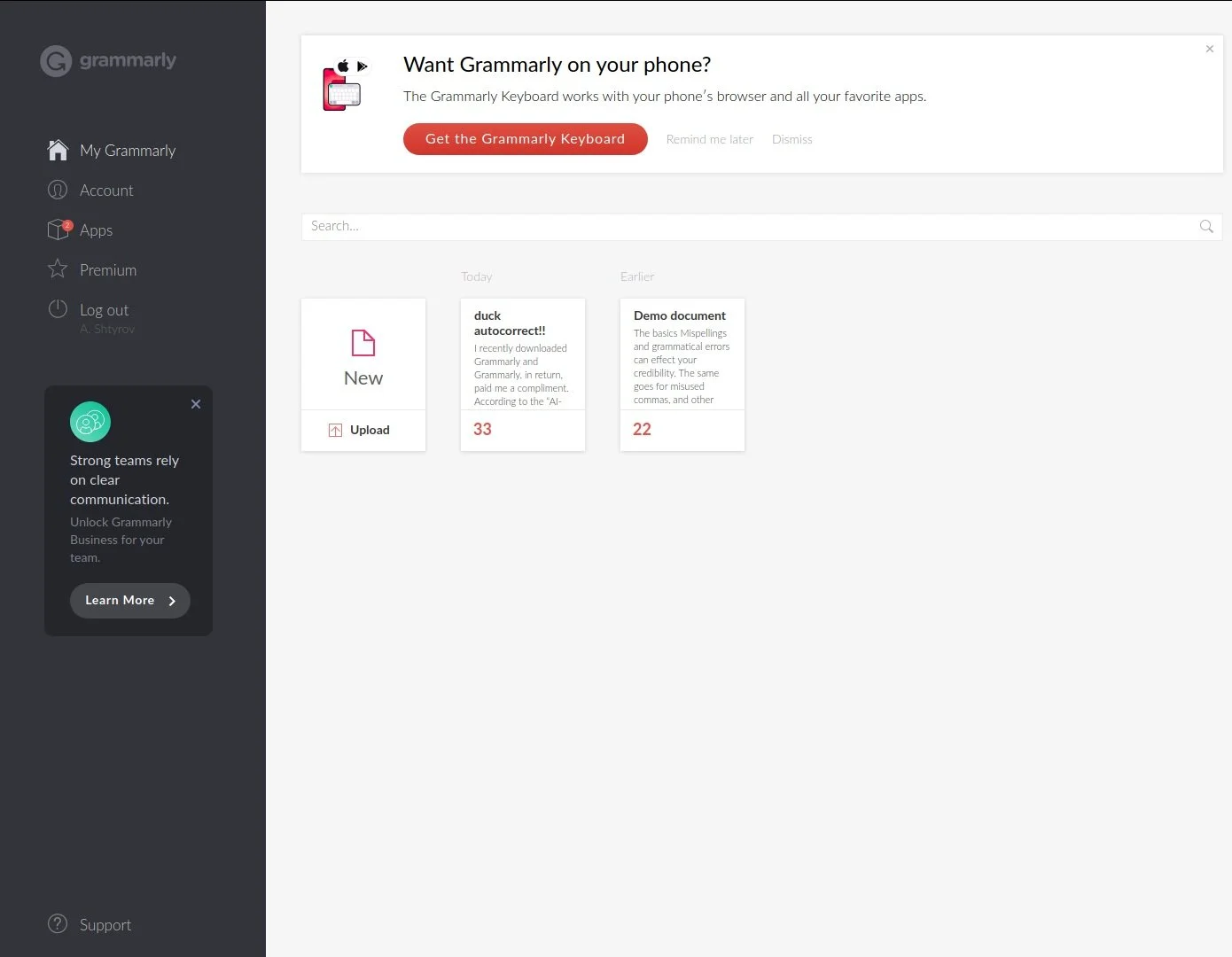

The service is easy to use and it took me less than a minute to sign up. After downloading the plugin, Grammarly made me create an account and choose the purpose of my writing. The dichotomy of choices - “School” and “Work”, are unsurprising, given the company’s target audience. I chose “School” because, whatever it is I’m doing right now, it isn’t a job. At the end of the process I was rewarded with a web app where I could upload texts and an incredibly annoying spinning circle on the bottom right of the Google Doc I am using to type this article. The colour scheme - a pulsating red, reminds me only slightly of Stanley Kubrick’s HAL.

“…a web app where I could upload texts…”

I was at first quite disappointed. When I signed up to Grammarly, I expected it to be bossy and intimidating, to grab me by the ear and lecture me on split infinitives and the use of ‘whom’. It was therefore surprising to find how lax the autocorrect feature was, at least in my short and distinctly unmethodical test run. Most of the errors are finicky grammatical points about the placement of commas [1] and articles [2] or the use of hyphens in modifiers. Great, but not exactly revolutionary.

Grammarly sometimes makes mistakes when suggesting corrections. On one occasion it suggested I modify

“Since understanding interactions is very important to understanding the function of a protein…”

to

“Since understanding interactions are very important to understanding the function of a protein…”,

which is clearly wrong. We don’t expect natural language processing systems to be perfect, but a program called Grammarly introducing grammatical errors into writing is hypocrisy at its finest. It is also quite satisfying on the part of the sceptical user.

“…grammatical points about the placement of commas [1] and articles [2]…”

“…cut tautologies […] [3], and remove supposedly unnecessary words (‘clearly’) [4].”

Stylistic ‘errors’ are detected more rarely, yet the texts I used were always shamed for excessive wordiness. The suggestions are rule-based substitutions that replace longer phrases with synonymous shorter ones (‘it is possible that’ has no place as a sentence starter), cut tautologies (e.g. ‘own’ after a possessive pronoun like ‘her’/’his’) [3], and remove supposedly unnecessary words (‘clearly’) [4]. In addition to ‘clearly’, ‘basically’ and ‘as a matter of fact’ are on the Grammarly blacklist. The wider context of a text is of course very difficult to incorporate into a rule, so as a result, words marked as unnecessary are not, in reality, always unnecessary. Sometimes, the meaning of a sentence changes when it is prefixed with one of these words, for instance by emphasising contrast. Sometimes, the tone changes. Much of the self-confident bearing of mathematics textbooks, for example, is caused by authors littering their writing with smug little adverbs. Remove them, and the intended authority is diminished. Sometimes, we might even want to include ‘unnecessary’ words not to change the meaning or the tone, but just for a little literary panache.

Remarks on the passive voice were notably absent from the list of suggestions, until I discovered that heckling about the passive is a premium feature. Students are often told that favouring the passive makes their writing more passive, and Microsoft Word tends to mark all uses of the passive voice as an error. I find this infuriating, so Grammarly Premium will have to wait.

Both Grammarly Premium’s features and, to a lesser extent, Word are marketed as being slick and modern. Behind the marketing speak, the emphasis is on writing that is efficient and easy to consume, optimised for a world in which readers do not have time to contemplate its aesthetic merits. Texts are hammered into arbitrary grammatical rules for the sake of standardisation. After all, an unnecessary ‘clearly’ wastes seven letters of space and at least half a second of time.

Prescriptivism is supposed to have fallen out of fashion. Nonetheless, Grammarly and its competitors have succeeded in repackaging it and putting it back on the market, under the guise of automated clarity. The emphasis - communicating efficiently rather than on stuffy Victorian ideas of grammatical correctness, is new, but the suggestions proposed by autocorrect software bear a striking resemblance to those found in published style guides. The presentation may be different, but the outcome - promoting linguistic homogeneity for the ‘greater good’, is very much the same.

Automated optimisations are conveniently best-suited to being performed by a computer. Computer analysis of language has a long and fruitful history. It is invaluable in corpus linguistics to analyse the changing patterns of language use, and has even found niches in literary criticism. Yet both of these fields recognise the strict limits of current-day software. A computer can count word frequencies in Shakespeare’s plays and report on the statistical differences in his works, but it will never comprehend when the characters speak with a hint of irony.

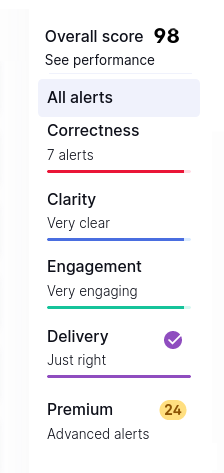

“Overall score: 98 out of 100.”

I do not demand that Grammarly carries out critical analyses, but even the most mundane writing has a significant pragmatic component. As writers, we may want to converge in style with our readers, or diverge from them, or carefully select the tone and register. To think that sentence-chopping, word-crunching programs can accurately assess the non-linguistic component of writing is naive.

At least I hope so, because Grammarly has some reservations about this article. Although it is well-delivered, the clarity could do with improvement. There are 7 critical errors, as well as 24 advanced alerts. Overall score: 98 out of 100.

![“…grammatical points about the placement of commas [1] and articles [2]…” “…cut tautologies […] [3], and remove supposedly unnecessary words (‘clearly’) [4].”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0d8984a97fa66e78f52bb7/1605706096735-L3F62QIILIX54OLOV59G/overall_score.jpg)