Lost Syllables and Found Debates

Book of Odes. (Image credits: via Wikimedia Commons)

In this article, all Old Chinese reconstructions use the system proposed in Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction by Baxter & Sagart (2014), though the hyphenation of pre-initial is after Hill’s book The Historical Phonology of Tibetan, Burmese, and Chinese (2019). As is conventional in historical linguistics, reconstructed (i.e. unattested) forms are given after * ; as conventional in Sinology, all Chinese characters are given in traditional (unsimplified) form.

I spent two weeks this summer attending a Zoom summer school about Chinese historical phonology. It was very technical and most of it went over my head – I am but an undergraduate in general linguistics. However, Chinese historical phonology is a very cool field of study, and I’d like to spend the next few minutes of your time telling you about some academic controversy about syllable structure in reconstructions of Old Chinese, more specifically the reconstruction of pre-initials, which is only one of the many interesting things I came across.

First off, some background. The Sino-Tibetan language family (Sino- being the prefix for China-related things) is a family of languages historically spoken in swathes of East Asia, most notably including modern and historical Chinese languages, Tibetan, and Burmese. As spoken languages, branches of Chinese have diverged from each other over the millennia, but through a shared logographic writing system, one Chinese-user can read what another has written without knowing what the author’s variety of Chinese sounded like. Phonologically, the most constant thing across Chinese languages is the syllable structure, which is roughly CV(C), plus lexical tone. This suggests the common ancestor of modern Chinese languages must have had this structure too. In Chinese linguistics, the onset consonant in this CV(C) structure is customarily called the initial, and the rest called the rhyme.

In their study of classical Chinese philosophy and literature, scholars throughout Chinese history have established extensive findings on semantic changes in the history of the language; stylistic demands of poetry meant that scholars also studied rhyming patterns in earlier forms of Chinese. This formed part of xùn gū (訓詁), the traditional form of Chinese philology focused on etymological exegesis based on historical documents. In contrast, there is also the Western methodology of historical linguistics, which gained explicit systematicity in the 19th century, and which aims to explain diachronic language change by postulating sound changes and comparing extant languages. The first application of Western historical linguistics to Chinese was by the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren in the 1940s, who made the first reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology, and opened up this field of study to Western philologists, and to Chinese researchers choosing to adopt this methodology. Thus, Chinese historical phonology ended up with two contrasting methodologies that didn’t talk to each other very much.

When applied to Chinese, the goal of (Western) historical linguistics is to reconstruct the sound systems of Middle Chinese (Chinese of ca. 7-8th c. CE) and, based on that reconstruction, Old Chinese (ca. 8-5th c. BCE). These reconstructions don’t point towards any actual language that existed at that time but is a hypothetical phonological structure which that era of Chinese would have had in order to explain any contemporary textual evidence, and the phonologies of its descendent languages. A European parallel might be the reconstruction of Proto-Germanic, which is the hypothetical ancestor of the modern Germanic language family. The main textual evidence for Middle Chinese comes from rhyme books compiled around the 7-8th centuries CE, which listed what characters were allowed to rhyme with what. Textual evidence for Old Chinese comes from poetry collections made around the 6th century BCE.

Now let me present the case of the reconstructed Old Chinese pre-initials.

Say you come across ‘Ode 235’ in the Shijing (《詩經》, ‘Book of Odes’), that reads like the following:

Ode 235 in the Shijing. (Image credits: Kitty Liu)

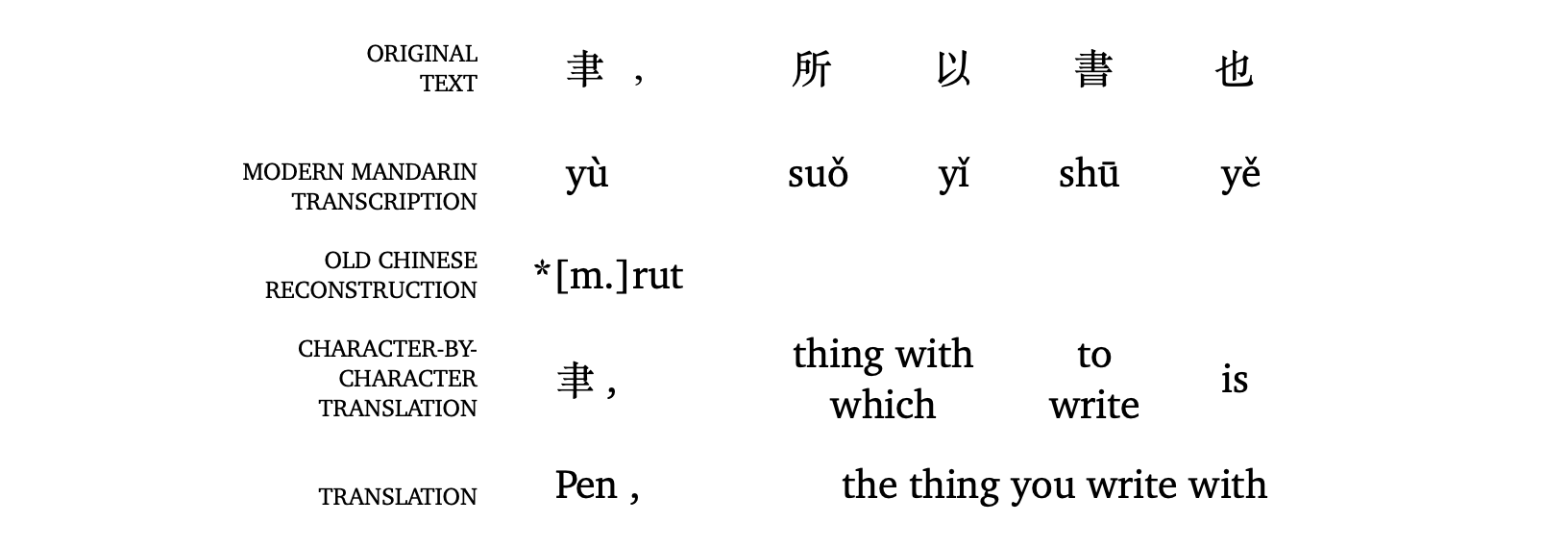

… and the Mao Commentary, one of the earliest Shijing commentaries dating back to the 3rd century BCE, says this:

Ode 235 in the Shijing, Mao Commentary, 3rd c. CE. (Image credits: Kitty Liu)

i.e., when it says, ‘don’t remember’, it means ‘do remember’ – which is not what the text seems to say, but does make much more sense. 無 (*ma) does the same thing in a number of other Odes, as does 不 (*pə), one of the other main negation markers in Chinese. The following is an example from the Shuowen Jiezi (《說文解字》, ‘Discussing Writing and Explaining Characters’), a 2nd century CE etymological dictionary that occasionally included material on contemporary dialectal variation:

Shuowen Jiezi (《說文解字》, ‘Discussing Writing and Explaining Characters’), 2nd c. CE. (Image credits: Kity Liu)

Here, the appearance of 不 (*pə) does not seem to be semantically relevant, but it does make what is a one-syllable word in Chu a two-syllable word in Wu. This is maybe a little odd, because the mainstream consensus on Chinese morphology is that historically, Chinese words were nearly all monosyllabic, as reflected in the fact that most words were written with a single character.

Traditionally, not much is made of these puzzling distributions of negatives. Their appearances in semantically relevant contexts, such as in the Ode above, are justified as rhetorical devices, such as ‘wouldn’t you remember your ancestors? ’.

However, an attempt is made to systematically account for these and other similar phenomena in Baxter and Sagart’s 2014 reconstruction of Old Chinese, where they propose a system of pre-initials: according to them, some Old Chinese words had prefixes that either surfaced as its own syllable (e.g. *mə-, ‘loose pre-initial’), or as an extra-syllabic consonant (e.g. *m-, ‘tight pre-initial’; it cannot be syllabified as part of the regular syllable initial because it is proposed as being morphologically distinct from the root, and it would in many cases violate the sonority hierarchy within the syllable). They are not normally written down because they are morphologically predictable, so speakers will fill them in when they read a character that should have a pre-initial attached. But in instances where poetic meter or pronunciation matters, they are transcribed: thus the stray 無 (*ma) and 不 (*pə) we see are instances when pre-initial *mə- and *pə- written down, ‘borrowing’ the characters normally associated with negatives. When the pre-initials were lost in spoken Chinese, it made no change to how Chinese was generally written: only these small traces of pre-initials remain.

This goes against all assumptions of what Chinese languages can look like. Being the textbook example of analytic morphology, Chinese is not expected to have prefixes. The writing system of Chinese characters is also based on a character-syllable correspondence, so the possibility of sometimes one character representing more than one syllable very much challenges what we think we know about the Chinese language.

Chinese historical phonologists in the Western tradition have been proposing one-off prefixes since Karlgren (specifically *s-), and in 1999 Sagart had proposed a different pre-initials system that intended to capture root structure and socio-stylistic variation. Baxter and Sagart’s reconstruction of pre-initials have been the most extensive and systematic so far, including seven pre-initial phonemes each with a tight and loose variety, and specific meanings for some of them (including *s- as causative, valency-increasing, and circumstantial; *N- as causing transitivity alternation; and *m- for animal names).

Classical philologists in China who work with xùn gū reject pre-initials, or indeed other reconstruction that include syllable-initial clusters and claim that researchers following the Western methodology have forgotten the fundamental characteristics of Chinese as a language. Western researchers in turn dismiss their scepticism as naïveté and close-mindedness for believing that there exist unchanging typological features that somehow preserve an essence of the Chinese language.

The Western historical phonologists have a point: as far as we know, no aspect of a language is immune to diachronic change, including morphological structure. However, that alone is not reason enough to accept Baxter and Sagart’s reconstruction: criticisms include that there are too many proposed pre-initials, and that textual evidence is not robust enough. I do not claim to understand the debate in any significant way, so as to have an opinion on whether Baxter and Sagart’s system is academically viable, but I do think the controversy illustrates some pitfalls concerning self-righteousness in science (inasmuch as historical linguistics can be called a science). The Chinese philologists claim to have a de facto better understanding of the Chinese language, simply because they have more associated cultural experience, and because they have bought into the notion of a temporal continuity in national identity and culture. On the other hand, the Western historical phonologists claim the methodological high ground, but risk extrapolating too much from too little. All the while, there is little constructive communication between the two camps, so that insights cannot be shared.

There is no choice but to advocate for academic ecumenism, even when goodwill is limited, and technical difficulties – such as language barriers and access to each other’s publications – are considerable. Ultimately, the phonological data we have of Old Chinese may not even lead us to the historically correct interpretation.

In the meantime though, I do find Baxter and Sagart’s pre-initials very exciting because it’s so different from even your average linguist’s understanding of the Chinese language. It’s exciting to see the kinds of new insights we can glean from ancient texts millennia after they were written, and it’s exciting to think that we may have gotten another step closer to understanding what it would have been like to be alive in the distant past.