Egyptian Soul I - Sayyed Darwish and the Struggle for Independence

Samuel Owers

Sayyed Darwish shortly before his death in 1923 (Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

‘Egyptian Soul’ is a reflection on music and history in 20th century Egypt. In a series of four articles, Samuel Owers examines key developments in the Arab cultural scene through three key artists: Sayyed Darwish, Leila Mourad, and Asmahan. Through their stories, he explores the past and present of Egyptian society, with all its contradictions and complexities. He touches on the clash of competing identities and allegiances (political, ethnic, religious) the role of women and marginalized groups, and the vast social changes that affected Egypt in this period, all through the medium of music.

1909

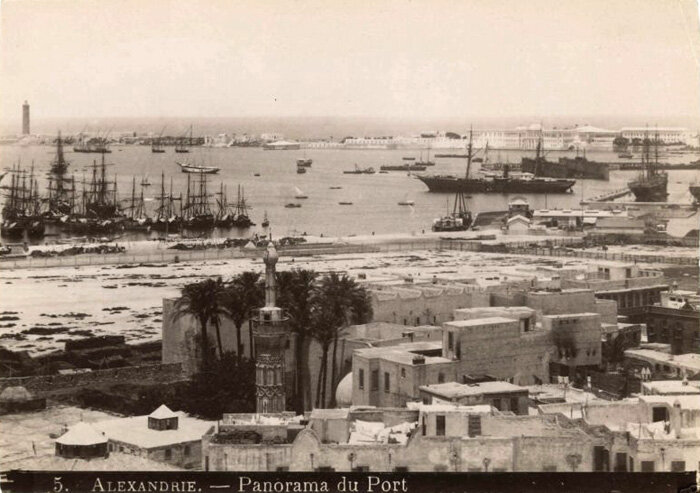

The port of Alexandria is one of the world’s great international cities, a strategic checkpoint on a global highway for goods, capital, and labour under the supervision of the British Empire. In its cafes and bars, Italian cobblers, Greek craftsmen, Syrian and Lebanese traders, Belgian capitalists, British officers, Ashkenazi doctors and Sephardi grocers gather and chatter in a dozen languages. Further ashore, alleyways lead away to sprawling neighbourhoods where ordinary Egyptians live. In the past few decades, capitalist economics, military occupation, and the beginnings of a modern state have brought unprecedented changes to their way of life, displacing the established social order. The result: complex stories which will capture the popular imagination for a century to come.

The port of Alexandria photographed in the late 19th century (via http://www.levantineheritage.com/alexandria.htm)

From one of these alleys a young man emerges, making his way by foot to the marina. At seventeen, Sayyed Darwish has lived several lives already. A carpenter’s son, he spent his childhood nights with his father’s friends in conversation and music. As a youth he travelled alone to Cairo, where he learnt the art of Quranic recitation at al Azhar university, earning the title of sheikh. He returned to his hometown to feed his family, working in a builder’s yard, but was excused from manual labour in exchange for singing to his comrades as they worked. Now, the aspiring musician prepares to embark on his biggest adventure yet: two trips to the Levant, spanning several years and traversing modern Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. When he returns, it will be as the maestro of his own ensemble, comprising some of the finest Arab musicians of his generation. The teenagers’s ambitions are as high as his interests are broad. He has mastered the classical tradition of the old Ottoman ruling class, and flirted with the music of Egypt’s latest occupiers, the English. One day he will even travel to Italy, to experience first-hand the spectacle of the opera.

1919

Unlike the case across most of her empire, Britain declined to declare Egypt a formal colony for the first thirty years of its occupation (1882-1914), instead preferring to rule indirectly through a Consul General, Lord Cromer. With an Imperial fleet patrolling the Mediterranean and tens of thousands of soldiers stationed throughout the country, the local government was powerless to reject the ‘advice’ of British officials. At the outbreak of the First World War, London finally decided to drop the act and declare Egypt a formal protectorate, using the country as a base for its operations against the Ottoman Empire. When the Paris Peace conference was called four years later, ostensibly to establish self-determination among the nations of the world, the Egyptian delegation was refused at Britain’s behest, and its ringleader, Saad Pasha Zaghloul, exiled to Malta. Incensed by the imperial powers’ hypocrisy, the Egyptians rose up against the British occupation in the Spring of 1919.

For the first time, men and women of all social classes joined in mass demonstrations across Egypt, hoisting banners which displayed the crescent moon of Islam and the Coptic cross side by side. This new conception of cultural identity, one which cut across class and community to encompass the nation as a whole, was at odds with existing musical currents, which were generally exclusive to social groups or ethnic communities. The favoured genre of the upper classes was the Ottoman-style dour or taqtouqa, performed by a virtuoso singer and a small ensemble known as a takht, and featuring classical Arabic poetry set to complex melodies on oriental scales. At the other end of the social scale were diverse folk traditions in the local dialect, employing a wider range of instruments and often tied to a specific locality or trade. Then came religious music, including sung passages from the Quran and hymns in praise of the prophet, performed at festivals celebrating the birth of Islamic saints (mawalid). To complicate the picture further, immigrant communities of Greeks, Italians, Syrians and English each brought a unique musical tradition of their own.

Women protesting with flags bearing the Islamic crescent and Coptic Christian Cross (Image Credit: http://mideastimage.com/photo/standard/Cairo-Demonstrations%201919.jpg)

Sayyed Darwish, now an established musician committed to the ideals of the 1919 revolution, made a conscious effort to unite the disparate strands of Egyptian music, and by extension Egyptian society, through a body of work which spanned classical poetry, romantic ballads, satirical monologues, and patriotic anthems. As his skills as a composer crystallised, he withdrew from performance, preferring to work alongside popular artists of his day. He would combine elements of different genres, taking melodies from protest chants and incorporating them into classical forms, or playing local folk music with a western-style ensemble. More than any other cultural figure, he is remembered as an icon of the anti-imperialist uprising and of the Egyptian independence movement. His revolutionary anthems ‘Oum ya masri!’ (Rise up, o Egyptian!) and ‘Aho dalli sar’ (That’s what happened) immortalised the events of 1919 and are still favourites one hundred years later, resonating especially since the Arab Spring of 2011. Less well known are his compositions in praise of women revolutionaries - a novel feature of the 1919 uprising - and Saad Zaghloul, the exiled figurehead of the revolution, the very mention of whom was banned by the occupying forces. To get around this military censorship, Darwish composed the ditty ‘Ya balah zaghloul’ in the voice of a fruit seller advertising dates, the words of which secretly allude to the revolutionary exile by playing on the double meaning of his surname.

1923

Five years after being exiled to Malta, Saad Zaghloul landed in Alexandria on the 15th of September 1923. It is one of the ironies of Egyptian history that on the same day, and in the same city, Sayyed Darwish succumbed to a mysterious illness, just as his revolutionary melodies were being chanted by crowds thronging the port. At the age of thirty-one, he had left a greater imprint on Egyptian music than perhaps any other composer in the twentieth century, affecting a revolution in songwriting that would send shockwaves throughout the whole Arab world, especially as Egyptian radio began to dominate the airwaves in the 1950s and 60s. Sayyed Darwish’s socially conscious innovations paved the way for artists like Umm Kulthum in Egypt and Fairuz in Lebanon, who were able to reach a broad cross-section of social classes by mixing classical and popular elements in their songs. The composers who helped to create these transnational icons – Mohamed Abdel Wahhab in Egypt, the Rahbani brothers in Lebanon – either studied directly under Darwish or cite him as a major influence.

Saad Zaghloul (Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Looking back at the events of the following decades, it is hard to know whether Darwish’s death was tragic or merciful. Though he was spared from watching Saad Zaghloul’s Wafd party repeatedly fail to liberate Egypt in the 1930s and 40s, he would not live to see another revolution in 1952 succeed in evicting the British from Egypt once and for all. He would not watch Gamal Abdel Nasser declare the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company from his native Alexandria, finally establishing Egypt’s economic independence, but neither would he see his hometown gradually stripped of its unique character as foreigners migrated or faced forcible eviction. He never knew that his composition ‘Bilady, Bilady, Bilady’ (My Country, My Country, My Country) would one day be installed as the Egyptian national anthem by President Sadat, but only once the peace process with Israel had made the previous anthem, ‘Wallahi zaman ya silahi’ (By God, it’s been a long time, o weapon of mine!) untenable.

Al-Ahram newspaper reports Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez Canal

2021

Alexandria may not be the diverse melting-pot of world cultures it once was, but its long seaside corniche retains something of its olde-worlde magic, especially if, like me, you’ve just arrived from Cairo, the hyper-congested, hyper-polluted megacity. Exhausted from travelling, I sit down at a seaside café and strain my ears to make out the tinny radio over the roar of the sea and the constant hum of microbuses whirring past. Now and again, I hear one of Sayyed Darwish’s compositions, though rarely performed by the man himself. His recordings, mostly from the early twenties, are few and far between, and sound quite abrasive to the ear no matter how shiny and new the sound system.

Alexandria’s corniche, as seen from the historic Citadel (Image Credit: Olivia Mustafa)

What if Sayyed Darwish hadn’t died in 1923? What if he’d lived to sixty, rather than thirty-one? Might Egyptian music have taken a different course? At the end of his life, Darwish became obsessed with introducing counterpoint to the Arabic musical tradition, which had always relied on a single, intricate melody. What if this experiment had succeeded? What if Alexandria had remained the diverse Mediterranean metropolis I see in black and white films? What if the 1919 revolution had succeeded in ousting the British thirty years earlier? What would Egypt look like now? It occurs to me that Egyptian history involves a lot of ‘what ifs’. As the sun sets, another Sayyed Darwish song plays: ‘Ana haweit w intaheit’: ‘I loved and was finished’. In a second, the what ifs melt away into the sound of the old radio and the waves breaking on the shore.