La Quête Queer I: Queer Self-Perception in the Films of Xavier Dolan

J’ai tué ma mère. Image Credit: Twitter

Columnist Miruna Tiberiu explores in her column ‘La Quête Queer’ queer life and culture in France. In her first instalment, she analyses perception and self-perception in Xavier Dolan’s films, and reflects on her own experiences.

I have never appreciated my MUBI subscription more than during my Covid-induced Christmas isolation. Shut away from the world, I spent Christmas with Xavier Dolan. I sat in my cramped Romanian apartment in his company, in a country which still reminded me of the scars of my coming out. Dolan’s characters gathered around me, comforting me. ‘It’s okay to fight yourself in your quest for identity’, they seemed to tell me.

Dolan’s films are teeming with this internal turmoil. His protagonists are all, without fail, thrust into a blur of transition, forced to become grounded after spending their entire lives in an aimless meander. It is their identities that they are forced to ground, from Laurence’s acceptance of her identity as a trans woman in Laurence Anyways (2012), to Hubert’s all-too-relatable task of wading through a meaningless teenage existence to find a reason for contentment in J'ai tué ma mère (2009). Dolan’s films are uncomfortable, borderline traumatic. We are forced into close-up after close-up on characters as they edge on breakdown, acknowledged as witnesses to this trauma through their repeated eye contact with us. We leave his cinematic world with no escape from this discomfort, no relief of a queer identity ‘achieved’.

Dolan’s characters are obsessed with how others perceive them, and their queerness. In Les amours imaginaires (2010), a seemingly mundane scene, a trip to a bookshop, becomes the acknowledgement of the vicious cycle of self-perception. Nico appears unexpectedly in shot. The camera languidly meanders around him, slowly settling on his face as he reads out from a book.

Image Credit: Les Amours Imaginaires (Xavier Dolan, Alliance Atlantis Vivafilm)

Quand dans l’amour je demande un regard, c’est qu’il y a de foncièrement insatisfaisant et de toujours manqué, c’est que jamais tu ne me regardes là d'où je te vois.

Nico is quoting Lacan, master of self-perception. Lacan’s concept of ‘logical time’ surfaces:two forces of ‘The Gaze’ are acknowledged here, ours, which we as Subjects are aware of as we perceive the Object of our Gaze, and the Gaze of our Other, who sees us as their Other, perceiving us at the same time as we perceive them. We have no insight into this latter process of perception, as it is carried out in a cognitive space that is not our own. This becomes the model by which almost all of Dolan’s characters attempt to figure out their queer identities. They put themselves in the imagined perspective of those who are gazing at them in order to understand how they are being perceived at that given moment, but also how their future actions, be it transitioning to a woman or coming out to a parent, will be perceived by these same onlookers. There is no shortage of tracking shots that follow characters from behind; I think immediately of Laurence, after a bar brawl, staggering back home. Our immediate perception of her identity matters less here than her internal quest of anticipating how others view her. It is only after the characters surround themselves with this vicious cycle, scrambling to figure out how the world sees them, that they can, slowly but surely, assert their identities themselves, in line with how they see themselves.

Image Credit: Laurence Anyways (Xavier Dolan, Lyla Films; MK2)

Image Credit: J’ai tué ma mère (Xavier Dolan, K Films Amerique)

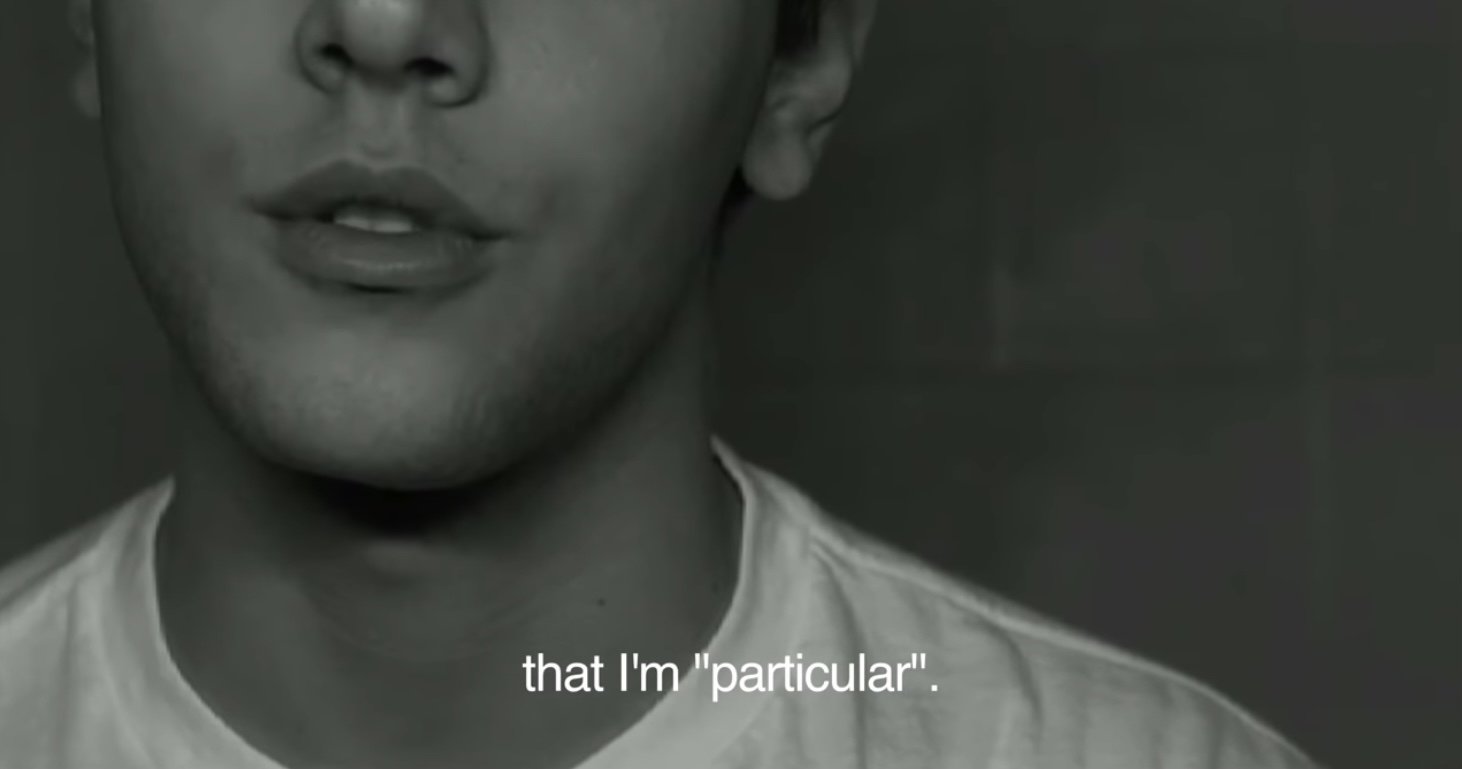

We often witness this cognitive process in disjointed, documentary-like sequences that deviate from the films’ narratives. In J'ai tué ma mère, we see Hubert, played by a fresh-faced 19 year old Dolan, being interviewed in the film’s opening. It is here that we gain insight on his mum’s perception of him, from her resentment of his very birth, which supposedly led to his parents’ divorce, to the way she constantly identifies him as ‘special’, which he takes to mean ‘weird’, ‘wrong '. How can he be comfortable with his own sexuality when living with a mother who resents his very identity? Around the midpoint of the film, our trust in Hubert’s portrayal of his mother’s perception of him is, however, completely thrown out. We see him walk into the bathroom with a camera; we realise that, all along, he has been filming himself, interviewing himself. With this, we realise that we have never been given insight into his mother’s gaze. All we know about his mother’s hatred for his identity now stems from Hubert’s anticipation of how the thinks his mother sees him. He is choked by the anxieties he feels towards the world, a hatred of his own identity.

Image Credit: J’ai tué ma mère (Xavier Dolan, K Films Amerique)

It is this that stops him from ever presenting himself as he wishes. He projects his self-hatred onto others. But we cannot blame him; in a world that casts to the margin everything that Hubert holds dear, his artistic pursuits, his existentialist views and, most crucially, his queer identity, we come to see this projected perception as a coping mechanism to avoid the real pain that would come with having his true identity be rejected. As much as he blames his mother, he is guilt-ridden. He tells us that he has killed her, ruined her life. Whilst J'ai tué ma mère ends without Hubert coming to terms with his queer identity, Dolan’s later films take things one step further. Laurence leaves the dingy bar, where she has made one last attempt to reconcile with her ex-girlfriend after twenty years of dealing with her inability to love her as a woman. Laurence’s trans identity transcends any attempt to mould herself into what her ex-girlfriend desires. As she leaves the bar, she is caught in a gust of liberating wind, the autumn leaves enveloping her. She is momentarily freed from the vicious cycle of projected self-perception.

Dolan tells me again that I can struggle, sometimes even for decades, to become comfortable with my own queer identity. Much like there is no beginning or ending to Dolan’s films, so my own quest for identity is a life-long project. After leaving isolation, with Dolan’s films swimming in my mind, I felt as serene as Laurence in her gust of leafy wind. I may not have entirely accepted my queer identity just yet, but I am ready for all the good and the bad that comes with this exciting life-long project.

Image Credit: Laurence Anyways (Xavier Dolan, Lyla Films; MK2)