The Will to Come: Intimacy, Transgressiveness and Contagious Bodies in Guibert’s Fou De Vincent

CW: pedophilia; homophobia; addiction

Gisele Parnall

Column I

Content warning: brief mentions of pedophilia, homophobia and addiction

Like never before, recent months have called for a radical reconceptualisation of what it means to be close to someone. In the intersection between a global pandemic and an era defined by displaced, technology-mediated communication, intimacy has been forced into reconsideration. Intimacy now necessarily relocates itself. Lest contagions flow from body to body, in the Covid-era we enact intimacy with one another on a mutual server, not in mutual space. New legislation deems bodies unfit for touching and so objects of desire are placed at a distance, departed, in some sense, detained. In the following articles, I would like to take a closer look at the sorts of intimacy which cross (or fail to cross) the boundaries of ‘contagious’ bodies. What does it mean for an intimacy forced into transgressiveness to operate in the face of disease?

Whether it be through lament or resistance, many French writers have spoken to the experience of carnal isolation, of bodies divided by contagiousness, and of the effort to transgress these divisions. In the still very recent past, France saw queer bodies eropolitically divided as a result of the AIDS pandemic. Intimacy which overcame AIDS had to transgress brutal homophobia, medical violence, and not to mention, the physical boundary of condoms. Fou de Vincent is Herve Guibert’s testimony to his tragic relationship with teenage Parisian l’homme du jour, Vincent, and their exploration of an intimacy which must attempt to coexist with the tragedy of addiction, internalised homophobia, pedophilia and AIDS. It explores an intimacy which must develop in the harshest of conditions, and in truth, struggles to really ever consummate itself. To my eyes, the intimacy which develops for Herve and Vincent reduces to a resistive oscillation between two poles which refuse to touch - a push and pull which defers the possibility of ever truly meeting, which prevents its own becoming, withholds itself, and which remains always at a distance. As the two men dance around one another, they refuse to ever really meet.

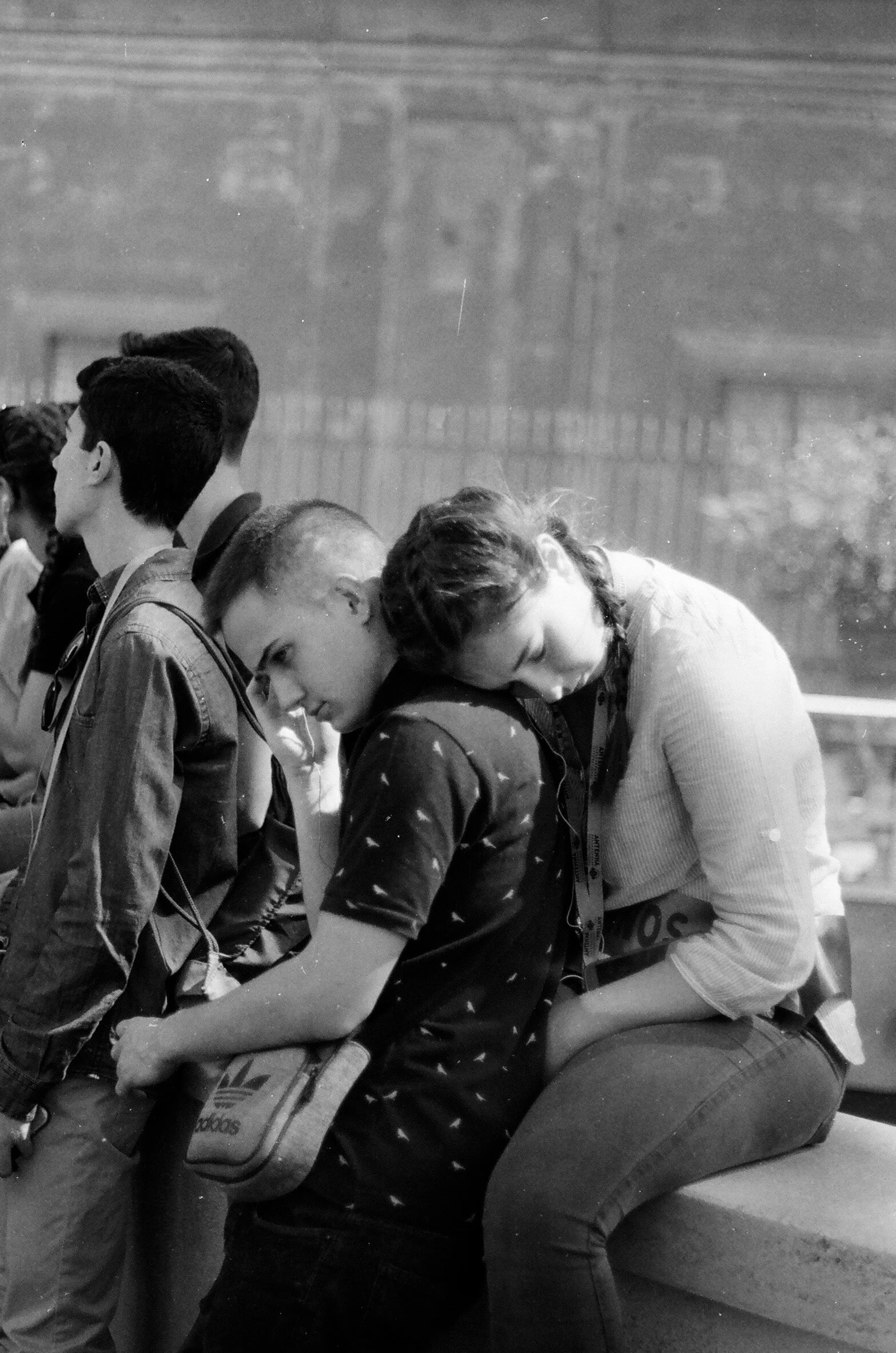

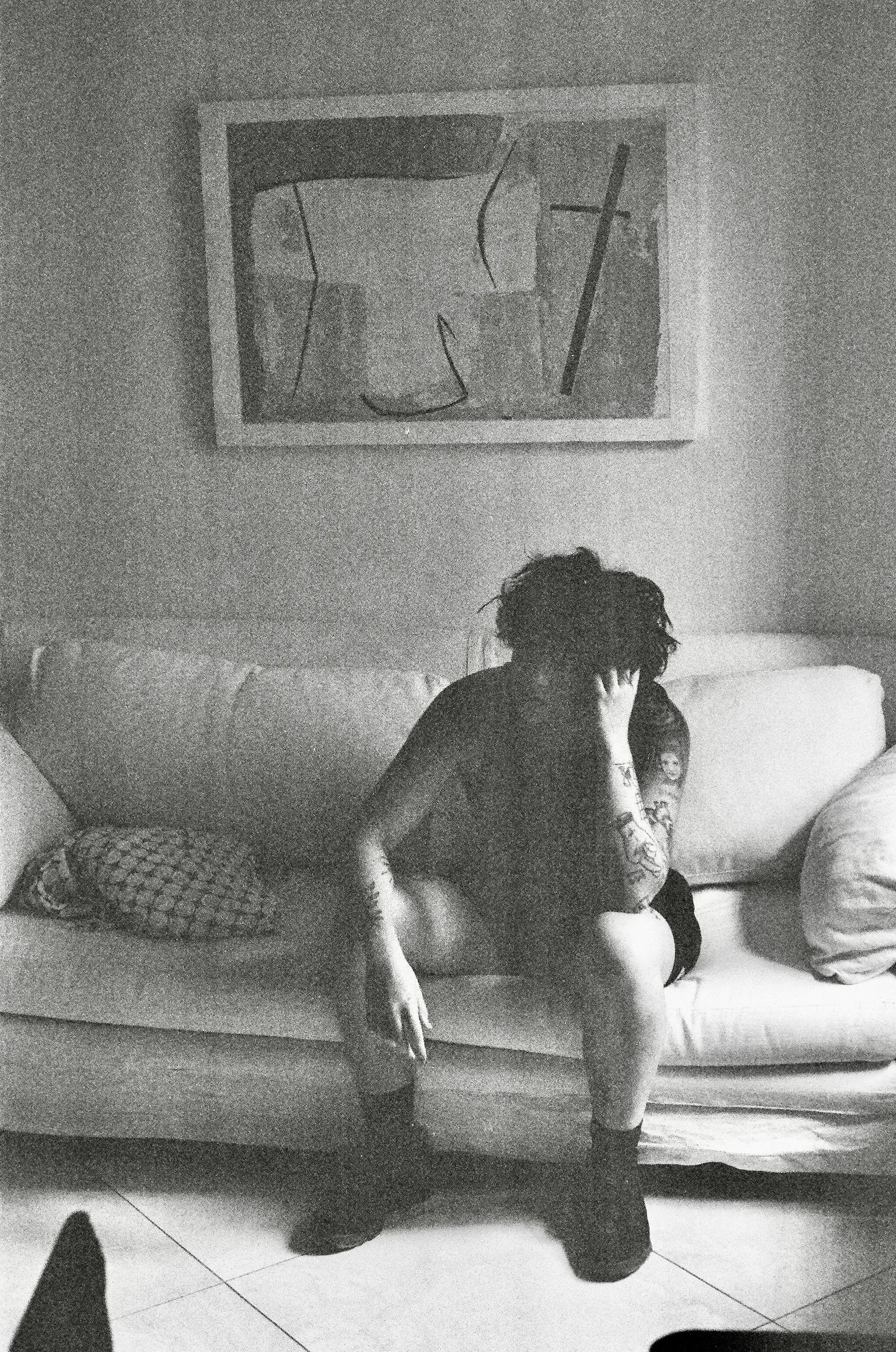

Photograph: Mia Parnall

Vincent didn’t show up…I have the suspicion that he deliberately wrecked the end of our last evening together because he had already decided not to meet me here; he would have figured that my resentment would mitigate my grief. He won’t come.

In fact, coming becomes a central motif of this novel. The limits of closeness between the two lovers are delineated by Vincent’s willingness to come (in both senses). The fulfilment of this contingency dictates their ability to be intimate with each other - for a refusal to come is a refusal to give yourself to the Other who demands your presence. The two men struggle with yielding to one another - Guibert writes: “I bless him every day for not having come here.” Giving yourself to another, coming for another, requires a relinquishing of your own will to stay, your own will to remain whole and one’s own boundaries. Coming ruptures stable boundaries - it shoots out, it abjectly defies the body’s delineation; it’s a violence. The Self (in all its fragility) must be dissolved to bond with the Other for whom it comes. In knowing this Other and coming for them and perhaps through knowing through coming, I transgress the boundaries of the Other - indeed, they too transgress mine.

In his exploration of the interplay between intimacy and transgression, Guibert returns often to skin as a signifier of the possibility to relinquish oneself. Skin, which undergoes touch, acts as a physical marker of will to intimacy through being in contact with the Other. But it becomes a corroded boundary for Vincent and Herve. The physical symptoms of AIDS begin to erode Vincent’s skin, and with that the two men must face a radically bonding intimacy - an intimacy of corroded boundaries - a love without borders.

Vincent upon returning from Africa: a leper. Holes in his skin, on his fingers, on his chin. Depigmentation of certain zones on his back. He scares me. He asks to sleep with me.

Skin, in both a visual, tactile, and metaphysical sense, is the watchman of human subjectivity. Didier Anzieu’s theory of Moi-Peau shows the relevance of the body’s surface in subjectivity formation; once bodies fail to be contained within this sheath by which we measure wholeness, identity becomes fragile. However, I would like to argue that in this case, the skin and its uncanny erosion allow the possibility of a profound new closeness for Herve and Vincent. It enables an intimacy which does not presuppose violation of boundaries.

Photograph: Mia Parnall

He asks me if I want to see his sores, I say yes, he takes off his shoes, he says, “Do you want to see the more disgusting foot, or the other one?” I reply, “The more disgusting one.”

These holes prompt a wounded Vincent to accept his vulnerability to an intimate penetration by Guibert. He welcomes this union where previously he has defended his wholeness with fervent resistance. Vincent craves what Andrea Dworkin terms skinless sex - a sex which denies transgressiveness, which allows two people to meet without violation. Skin is a boundary to intimacy as it requires sex to break borders. What we see in Fou de Vincent is a move towards resistive sex. An intimacy which encounters no skin and progresses anyway. Vincent yearns for total closeness - “He wanted to take off the condom.” He wants to remove the synthetic sheath demanded by AIDS which functions to divide the two lovers. This substitutive layer signifies the political quarantining of the AIDS subject - the AIDS ‘victim’ is denied an intimacy deemed infectious. The uncanny artifice which Vincent must wear becomes an obstacle to the intimacy which these men desire to share. They wish to free their bodies from this phallic quarantining - they wish to overcome contagiousness.

I suppose, the question that is raised is the extent to which intimacy requires us to relinquish our own boundaries. Is total union (a dissolving of borders) necessary for intimacy? Is this inextricably linked to a view of intimacy as inherently physical, or tactile? Can we in fact cultivate intimacy whilst upholding the limits of our own subjectivity? I would like to argue that rather than presupposing some sort of transgression, intimacy is a willingness to meet in the middle, to both extend one’s own boundaries for the sake of love’s synthesis. What I think Guibert demonstrates in Fou de Vincent is the necessity of willingness. When one is willing to come, when one stops resisting, intimacy must no longer be transgressive.

Vincent said to me, I have a fungus, he said, I have scabies, he said, I have a sore, he said, I have lice, and I pulled his body against mine.