Balancing Act: The Fight on Violence against Women and EU Legislative Authority

The European Commission (Cancillería Ecuador, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

In anticipation of the upcoming European Parliament elections this year, the first ever EU-wide legislation targeting violence against women has the potential to alter the legal and political landscape of this deeply entrenched issue. For the last two years, the European Commission has been trying- and failing- to implement a directive applicable across all EU member states that codifies non-consensual sex as rape. Each member state would have to transpose the legislation into their own national laws for it to take effect. The proposal was rejected in June 2023, with EU governments generally supporting the directive, except for the provision on rape. While in today’s social climate it is widely accepted that any sex without consent is rape, in 14 EU countries (including France and Poland), the onus is on the victim to prove the use of violence or threat against them by the perpetrator. The reluctance of national governments to support this legislation raises questions not only about how seriously these governments treat crimes of sexual violence against women, but also about the role of the European Union. Should the EU have jurisdiction in the criminal law of its member states? The issues posed by this draft reform are a debate between the legitimacy of the extension of legislative authority by Brussels and the continued fight against an ingrained culture of misogyny in European politics that refuses to treat the issue of violence against women with the gravity it merits.

This draft law, presented by the European Commission in March 2022, aims to prevent and reduce all forms of violence against women. This includes female genital mutilation, forced marriage and cyber violence (such as “revenge porn”). It is the provision about rape, however, that is causing contention. This proposal follows on the heels of the ratification of the Istanbul Convention by the European Union. Formally known as the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, the Convention is the first legally binding instrument in Europe that specifically focuses on combating violence against women. It defines rape as non-consensual sex. While the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) does not explicitly mention rape, victims can bring cases to the European Court of Human Rights asserting a violation of their fundamental rights under Article 3 of the ECHR, which states that ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.’

Berber Biala-Hettinga, an advocate for human rights with Amnesty International maintains that ‘sexual violence continues to ravage the continent and the world’. A recent survey conducted by the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) reveals that 11% of women in the EU have experienced some form of sexual violence from the age of 15, and 5% have been raped after the age of 15. It is likely that these figures are a substantial underestimation. The potential of a blanket legislation that (re)defines sex without consent as rape and removes the weight of responsibility from the victim could be a significant advancement for women’s rights within the EU, working towards the destigmatisation of rape and greater conviction rates for the crime.

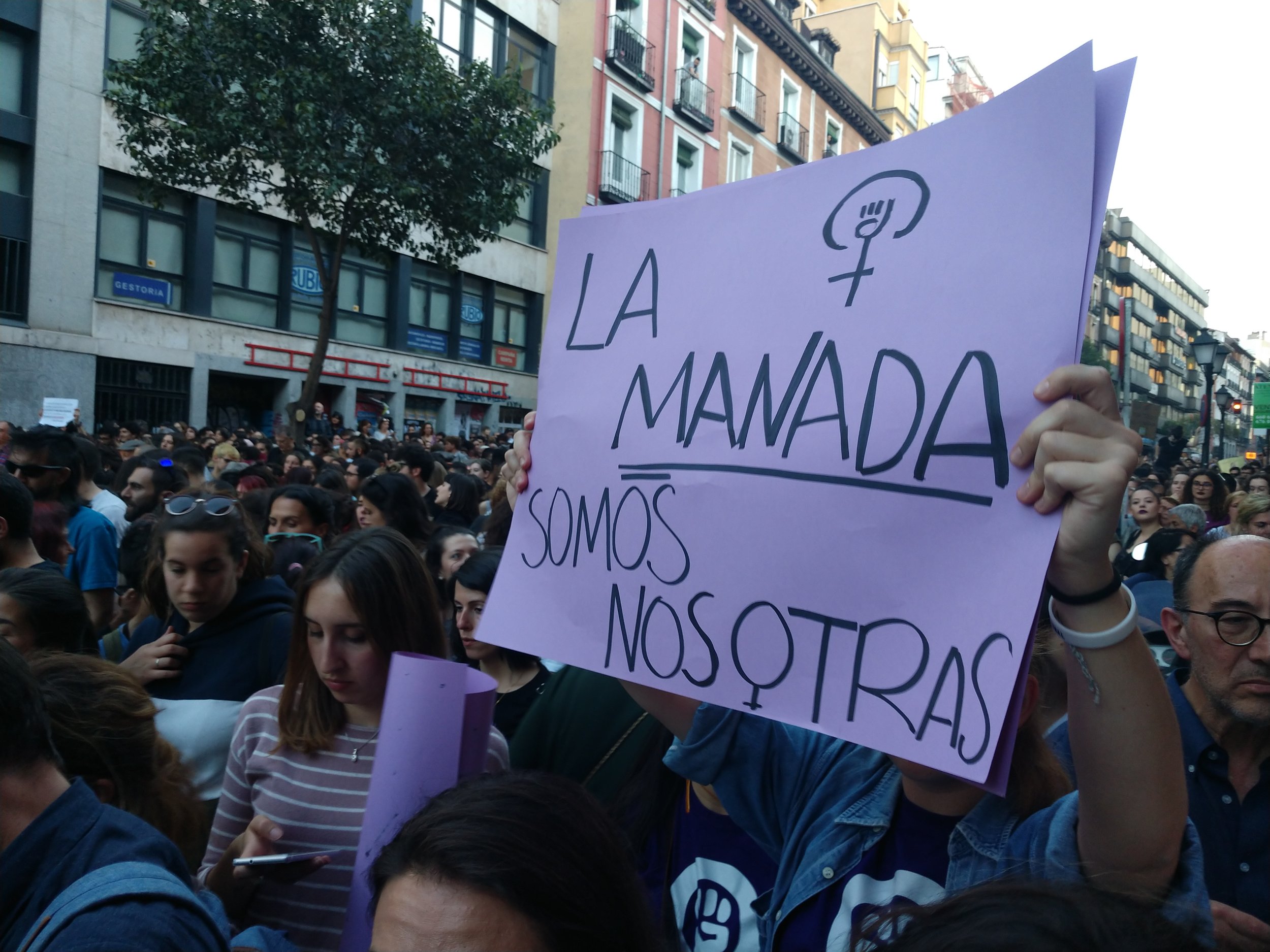

ProtoplasmaKid, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In some EU countries, the legal definition of rape is already based on consent. In Spain, this is a fairly recent development directly related to the severe mishandling of the La Manada (The ‘Wolf Pack’) case. During the San Fermín celebrations in Pamplona in 2016, five men gang-raped an eighteen-year-old woman. Due to the nature of Spanish criminal law at the time it was not until three years later when they were convicted of rape in the Supreme Court sentencing. As it was deemed that the victim could not prove the use of violence against her, the five men were found guilty of sexual abuse, not rape. In response, the Cortes Generales passed the Ley de Libertad Sexual (also known as the Solo sí es sí law), which classifies all non-consensual sex as rape. While this seems like a victory for women’s rights, this reform has backfired. Its implementation caused automatic sentence reductions for several previously convicted sex offenders, including, paradoxically, some of the members of La Manada. The very rapists who inspired this law are now benefiting from it. The enactment of a similar EU-wide law is undoubtedly a source of concern, considering how dysfunctional its execution has been in Spain.

Another complication that arises from this draft legislation is centred around the role of the EU and concerns about the expansion of its legislative power. Should the EU be granted this power and presence in national criminal courts? There are various EU-wide policies that apply across all member states, such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), environmental legislation and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). However, an EU-led codification of a criminal offence is seen by many as a step too far. The expansion of EU jurisdiction has the potential to undermine the rule of law in the member states and to fuel anti-EU political movements within them. The debate surrounding this draft legislation puts into question the role of the EU, and whether its presence in domestic courts is legitimate.

Due to the very nature of this draft legislation, its focus on violence against women and its blanket applicability, it will not be passed. This will only be reinforced with the European Parliament elections in June. The proposal of this directive has revealed a balancing act in the EU, between the need to increase legal protection for women and the importance of national sovereignty in the area of criminal law. The need to push further in the fight against gender-based violence is incontestable. Italian Prime minister Giorgia Meloni’s answer to the recent gang rape of two young girls in Naples has been to allocate 10 million euros to repair the abandoned sports complex where the assault took place, rather than tackle the glaring issue of rape culture in Italy head-on. This crime has to be treated with far greater severity than it is. However, this proposed legislation may not be the most effective way to ensure this. As demonstrated in Spain, the way in which this codification is enacted can prove hugely problematic. The fight against sexual violence remains an issue that national governments, spurred on by the Istanbul Convention, must address themselves, as a matter of urgency.