Alberto Giacometti - the terror of the human condition and the endlessness of artistic quest

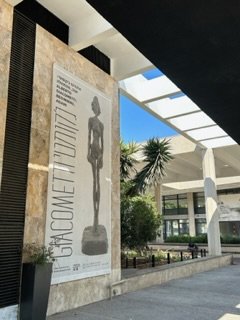

‘Alberto Giacometti, Beginning, Again’ - Eyal Ofer Pavilion, Tel Aviv, Israel (Photo: Einav Grushka)

Born in 1901 in the Swiss village of Borgonovo, Alberto Giacometti came to be known as one of the 20th Century’s most notable artists, forming an integral part of Europe's most significant artistic and philosophical circles and mixing with the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Samuel Beckett. Having moved to Paris in 1922, the young artist exhibited an interest in Cubism, interacting with fellow artists Miró and Picasso. In the late 20s, drawn by themes of the subconscious and abstraction, Giacometti was welcomed into the Parisian Surrealist scene by the writer, poet and primary thinker behind the Surrealist movement and the Surrealist Manifesto, André Breton. Until his expulsion from the group in 1935, Giacometti produced a significant body of work evoking abstraction, dream-visions and Freudian-esque anxiety-inducing images of violence and sex before returning to work with live models and nature. In other words, before landing back in the realm of the real.

Despite his wide generic range, Giacometti’s trademark in the art-world to this day remains his post-war opus. His sculptures from this period, characterised primarily by impossibly thin, tall and gaunt figures, were inspired by existentialist thought. Through his art, Giacometti emphasised the loneliness, terror and meaninglessness of the human condition, as well as the impossibility of artistic perfection.

The exhibition, ‘Alberto Giacometti, Beginning, Again’ displayed in cooperation with the Fondation Giacometti at the Eyal Ofer Pavilion in Tel Aviv, offers an array of Giacometti’s works, curated in an organically progressing and astute manner. Across the four floors of the exhibition, viewers are guided chronologically through Giacometti’s stylistic evolution.

Given the primary focus on Giacometti’s post-war opus, entering the gallery to works reminiscent of Picasso’s cubism and Dalí or Magritte’s abstraction is rather surprising. Far removed from the fragility of the slender sculptures he is known for, the first room of the exhibition houses confrontational totemic sculptures. In Composition (1926-7) a faceless coupled figure is constructed of sharp angles and straight, brutal lines, removing any sense of subjectivity from the bodies. Moreover, the murkiness and opacity of the bronze is rather striking in its inhumanity. In The Couple (1926) Giacometti experiments more with facial structures and gender distinctions. Despite the clear angular distortion, features such as eyes, ears and mouths are discernable, albeit in abstract arrays and perspectives, somewhat similar to Picasso’s Woman with Artichoke (1941). Moreover, the ovular shape of the feminine figure as opposed to the stiff nature of the masculine one are clearly vulvar and phallic in essence, drawing upon the thematics of desire and sexuality in a detached, abstruse manner.

Composition (1926-7) (Photo: Einav Grushka)

The Couple (1926) (Photo: Einav Grushka)

One of Giacometti’s most significant contributions to the Surrealist movement was his powerful and angsty sculpture, Point to the Eye (1931-2). A stinger points to the eye of a minuscule skill adorned with rib-like bone structures. Reminiscent of the opening scene of Dalí and Buñuel’s film Un chien andalou (1929), in which a cloud seemingly crossing the moon transforms vehemently into a razor slicing open a woman’s eye, Giacometti brings to the fore hair-splitting visions of danger and pain. In this particular sculpture, the phallic nature of the stinger emphasises the common Surrealist juxtaposition of desire and death, pleasure and pain. These works aim to trigger reactions of shock, confusion, and often both simultaneously.

Point to the Eye (1931-2) (Photo: Einav Grushka)

By contrast, Giacometti’s post-war sculptures, although equally evocative, provoke reaction in more understated and sinisterly quiet manners. They are subtly disquieting. Giacometti’s art transforms from being a poignant display of art for art’s sake, detached from reality and rational consciousness, to displaying contemporary social anxieties and the sense of aimlessness, solitude and nihilistic destiny instilled in society by the end of the war.

In the wake of the Second World War, Giacometti’s sculptures became emblematic of existentialist thought, illustrating man as trapped between life and survival, being and nothingness, as Sartre put it. William Barrett suggests that Giacometti’s figures became synonymous with a modern life devoid of meaning (Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy). Many of his sculptures give the impression of incompleteness or imperfection. Half-Length of a Man (1965), beyond clearly insinuating noncompletion in its title, loses detail and precision towards the foot of the sculpture, as if melting into its base. Not only are the figure’s features seemingly incomplete, unvarnished and granular, it also seems in a constant state of deterioration.

Half-Length of a Man (1965) (Photo: Einav Grushka)

This state of imperfection and hopelessness mirrors the lack of psychological catharsis offered to man, symbolising the permanent state of human anxiety. In Composition with Three Figures and a Head (1950) the sense of depression is evident through the figures’ sunken faces and skeletal bodies. Most striking is the grotesque platform on which they stand. The fact that the bases seem to form a single mound or foot, implies the lack or even impossibility of movement, as if the figures portray a stasis that condemns them to entrapment, with no chance of escape, rather like the motivic entrapment in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play Huis Clos (No exit).

Composition with Three Figures and a Head (1950) (Photo: Einav Grushka)

Tall Nude (c.1961) is a prime example of the sense of entrapment and impending doom maintained in Giacometti’s paintings. Beyond the fact that the figure’s arms are drawn tightly into her body, illustrating restraint, the darker slash-like strokes around her legs and ankles resemble chains. The violence and melancholy of this image suggests desperation, rendered stronger and more devastating via the translucent nature of the figure’s body, as if hollow and lifeless, as well as the menacing cloud of grey and black that enshrines her body. In other works such as Yanihara Seated Full-Length (1957), the figure’s face and head are disturbingly blacked out, resonating with ideas of failing humanity.

Tall Nude (c.1961) (Photo: Einav Grushka)

The gallery that houses Giacometti’s post-war sculptures and paintings in the Tel Aviv exhibition is cleverly made to resemble an open city square. It is filled with figures in close proximity, and yet, they all face different directions, accentuating a certain loneliness within the multitude. Man ends up alone, helpless and fearful no matter how embedded he is within a community. I was lucky enough to be almost alone in the room during my visit, an experience which accentuated the ambience of overwhelming solitude.

Eyal Ofer Pavilion, Tel Aviv - The Square (Photo: Einav Grushka)

As the exhibition’s title suggests, Giacometti never felt as though his works were complete or perfected, always returning to tweak them, beginning again and again. It is precisely the endlessness of this artistic quest that mirrors the cyclical entrapment of the figures he depicts. Just as represented in his sculpture, The Cage (1949-50) Giacometti suggests that man seemingly has nowhere to go, looking out into the open and yet chained to the ground. The lower level/base of this sculpture symbolises the only movement he sees as viable: the descent into death and damnation.

The Cage (1949-50) (Photo: Einav Grushka)