Please Pardon our French

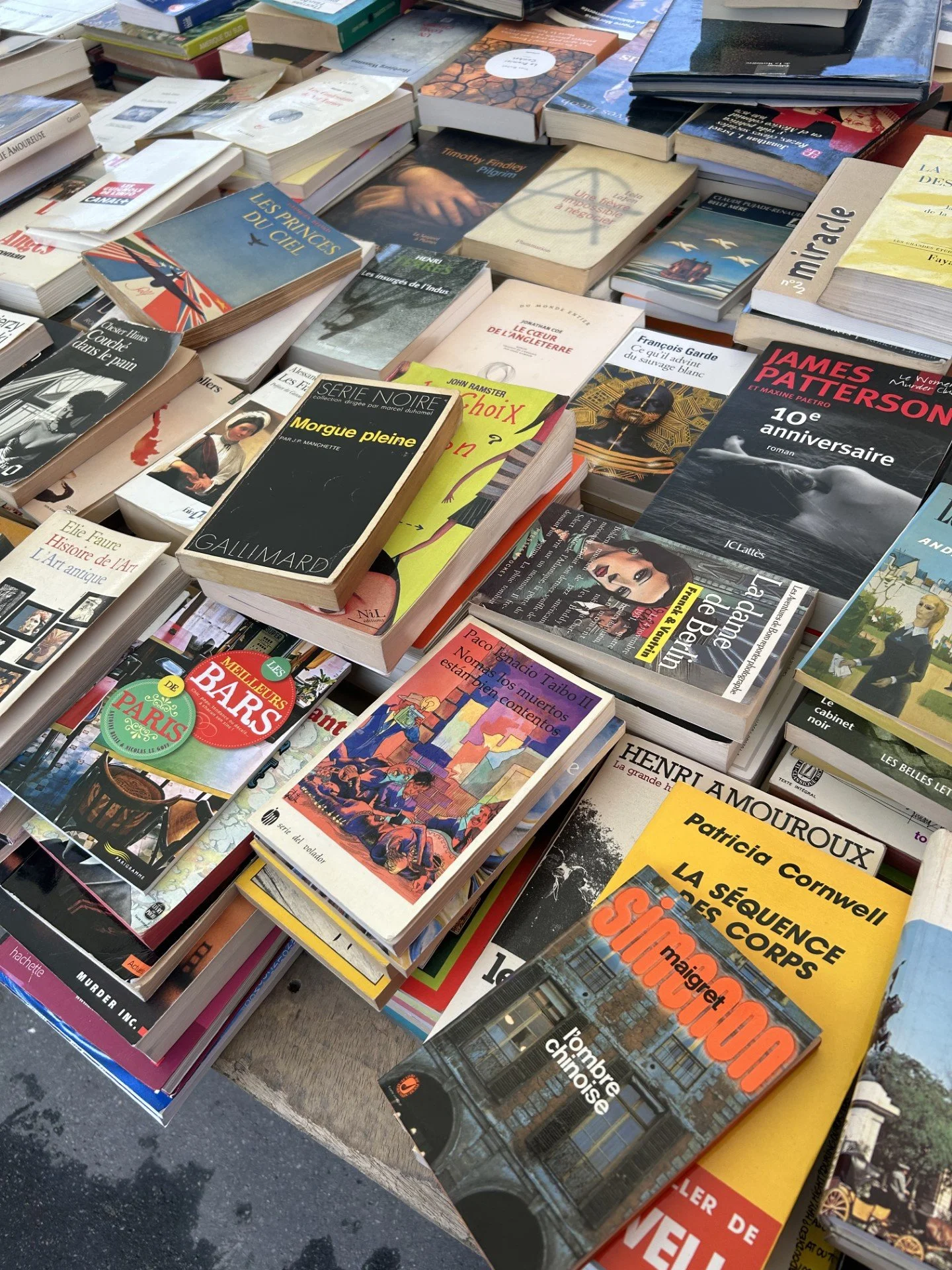

Book stall at the Brocante Puces de la Place d’Aligre. All images belong to author.

‘Sorry for my English’ is a phrase I have encountered several times since living in France, and it is one which—perhaps paradoxically—brings me embarrassment. French students my age will insist on their need to practise their English all the while perfectly following the colloquialisms, nuances, and cultural references of anglophone conversations. It seems that what is considered merely a satisfactory level of English amongst the French is, in fact, a bilingualism that most Britons can only dream of and, likely, will never achieve. Perhaps due to our dark colonial past, or simply because of our geographical separation from continental Europe, Britain is plagued by a chronic aversion to valuing other languages. Despite the historical linguistic enrichment of the English language by European invaders, our nation seems to suffer from a peculiar, and concerning, resistance to foreign language learning. For passionate linguists, pro-Europeans, and anti-Brexiteers alike, this is a troubling reality.

Rishi Sunak’s A-level revamp purports to improve young people’s professional prospects, allegedly ‘giv[ing] them the skills they need to succeed in the jobs of the future.” However, Sunak’s plans possess a crucial flaw; in the hierarchy of ‘essential’ subjects English and Maths rule supreme, whilst modern languages are, once again, cast aside and overlooked. In an increasingly globalised world, multilingual dexterity is arguably the most important skill of all. What’s more, if you work within a multinational corporation, the chances of you needing to communicate with someone who doesn’t speak your language greatly exceed the chances of you needing to perform advanced trigonometry.

This country’s continental aversion has consequently produced a systemic deficiency in foreign language capabilities and the inability of many Brits to see the value in learning another language is reflected in the (a)pathetic attempts to include them in our school curriculum. In contrast, for the French baccalaureate —the equivalent to A levels—every student must study at least one language until they leave school; multilingualism is a necessity rather than just an added bonus. So, in a world where—quite literally—it pays to be bilingual, the British education system has rendered us insipid employees in comparison to European neighbours.

The value of multilingualism then extends even further, beyond the matter of empirical profitability ; there is an intangible value that accompanies the ability (or indeed willingness) to speak a foreign language, a sort of social currency. I’ve watched as brash tourists in Paris ask wait staff or shop assistants: ‘Do you speak English’ without so much as an introductory ‘Bonjour’ or ‘Ça va?’ In a country where savoir-faire is of the utmost importance (‘faire la bise’ requiring its own instruction manual, for instance) this is a faux-pas which clearly antagonises the locals. Although it may well be the case that practically everyone in Paris does indeed speak English, there is an arrogance in the assumption that this should be the case. Speaking the language of a country you’re visiting does more than simply making ordering in restaurants easier, it predisposes locals to wanting to help you, and there is a certain, invaluable, camaraderie that linguistic mutuality offers. The (stereo)typical Parisian who is impolite and unfriendly may still exist, but —undoubtedly— their acerbity is far less severe for those who try to speak French, rather than those who deign to.