Do Our Cities Reflect us? Monumentalism, Murals and Memory in the Former USSR

Alice Mee

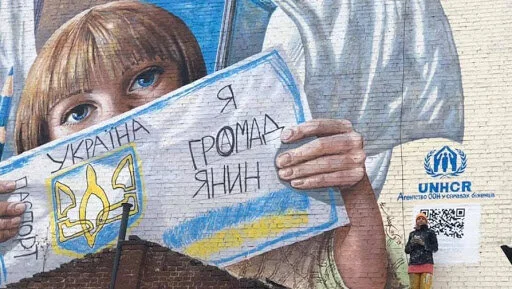

Kateryna Rudakova, ‘Little Citizen’. 2009

UNHCR/Ukraine

Arriving into Kyiv city centre from the airport, you are greeted with a forty-eight-metre-high mural of a ballerina balancing on a bomb. Subtle it is not. Entitled ‘Instability’, in reference to Ukraine’s ongoing hostilities, this is just one of the many murals created in post-2014 Ukraine, adorning everything from apartment blocks to offices to embassies.

Murals may be popular the world over, but post-Soviet countries have a very particular inheritance when it comes to art in the public sphere. When you picture the formerly ubiquitous monumental Soviet murals, it is easy to dismiss them as mere propaganda, deifying national heroes and inspiring collective feeling. Despite this, I believe the artistic value of these murals continues to resonate. For Soviet iconography is certainly distinctive, but it is not hard to perceive the influence of Orthodox iconography, or even abstract, experimental movements in certain examples. This is just one of the reasons why I believe it is near impossible for a country such as Ukraine not to be influenced in some way by Soviet art; doing so would necessarily mean rejecting much of its pre-Soviet heritage.

Nowadays, post-Soviet urban spaces are the site of both new artworks and their predecessors. Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova’s 2013 exhibition, ‘Monumental Propaganda’ tackled this coexistence by immortalising the usually transient visual images of our time in typically Soviet mosaic techniques. This provocative reappropriation of the Soviet inheritance reveals a conflicted historical memory, expressing a desire not to erase all traces of former regimes simply because they clash with the modern status quo. Kadyrova's message turned out to be timely: many Soviet mosaics across Ukraine were hastily taken down following the 2014 Revolution of Dignity and a 2015 law on decommunization. But Kadyrova is not alone in wrestling with such a clean break from the past. In 2017, Ukrainian cultural platform Izolyatsia called for the preservation of such murals, arguing that, regardless of ideology, they are still part of Ukrainian heritage.

Zhanna Kadyrova ‘Monumental Propaganda’, 2013/Ruslan Kolmykov

In contrast, many modern political murals take a different view, explicitly rejecting the Soviet inheritance and reappropriating the public space to push a pro-European agenda. Take the 2015 mural of Serhiy Nigoyan, the first activist to be murdered in the 2014 Euromaidan. This mural is innovatively carved into plaster, and fittingly overlooks a memorial to those lost in the Revolution. The human impact of hostilities is again highlighted by Kateryna Rudakova in her 2019 ‘Little Citizen’, depicting a child clutching a homemade Ukrainian passport, in reference to the tens of thousands displaced by the war in east Ukraine. This image was actually inspired by true events, namely a Crimean boy who drew himself a passport, transformed by the artist into a symbol of the inequalities prevalent in displacement. Such politically charged murals go one step further than Kadyrova’s exhibition, transforming a Soviet legacy into a means to push an anti-Soviet, anti-colonial agenda, questioning ongoing Russian aggression.

As changes in attitudes towards the Soviet legacy appear to have accelerated in the aftermath of the 2014 Revolution, it is interesting to consider how the role of art in public spaces in Belarus may change following the current protests. Despite restricted freedoms, murals with political undertones have appeared, including the 2019 mural depicting Putin and Lukashenko embracing, in clear reference to the Berlin Wall’s ‘Fraternal Kiss’. Indeed, although many such murals are quickly painted over by the authorities, protestors have recently started to resist this: one mural of two DJs who have taken part in this year’s protests has been painted, then covered, then repainted more than a dozen times.

The events in Belarus have equally caused ripples in other countries, as shown by a mural painted in St. Petersburg in September this year, only to be covered the next day by the authorities. Using the red and white associated with the popular movement in Belarus, the mural references traditional folklore: a woman on a white wolf – a symbol of Belarus – escapes from a captor, while another woman remains in chains, symbolising Russia (according to the artists). Not only does this clearly pay tribute to the role of women in this year’s protests, but it also demonstrates that, although painted murals may be more short-lived than their mosaic Soviet counterparts, this perhaps affords them greater immediacy and relevance to their time.

While our country wrestles with the legacy of the past in the form of monuments, with the fall of Bristol’s Edward Colston statue making headlines this summer, we are not alone in turning to monuments as a symbolic rejection of the past. In fact, the image of the empty pedestal in Bristol has striking parallels with the Ukrainian phenomenon of ‘ленінопад’ (literally ‘Leninfall’). The base where Lenin formerly stood in Kyiv remains to this day, at one point adorned by a golden toilet (!) in reference to the notoriously corrupt ex-President Yanukovych. This is a reminder that the statue’s removal was not ‘the end’, but rather part of the constant adaptation of the public space to our changing world.

Even before the dramatic fall of many Lenin statues in 2014, Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan’s 2009 work, ‘Pedestal. Practice of exclusion’ (‘Постамент. Практика витіснення’), an enormous model of a statue-less pedestal, questions the purpose of such monuments. Reaching the gallery ceiling, and leaving little space for movement around its base, it highlighted the meaninglessness of statues themselves, when their true purpose is more an assertion of power. White text documents what the artist terms the ‘War of the Monuments’ in post-Soviet Ukraine; vandalism of both Soviet and new monuments. So, paradoxically, this work is a monument to monuments, demonstrating the ongoing difficulties of collective historical memory in Ukraine.

‘Pedestal. Practice of Social Exclusion’, 2009 /Nikita Ka

Belarus has historically taken a different approach to Ukraine in this regard: the authorities revealed a newly renovated Lenin statue in Minsk in 2016. This statue was, paradoxically, the site of some of the first protests against Lukashenko’s regime this summer. Interestingly, journalists have reported that issues such as decommunization are not high on the protestors’ agenda, prioritising above all Lukashenko’s removal. So, is there really a need to erase remnants of the past? Indeed, whilst art in the public space is not enough to bring about change on its own, it is worth remembering that objectivity and psychological distance is needed for reminders of the past to simply become a part of history, detached from their ideology.

So, do our cities reflect us? And does it matter if they do not? Popular movements across the post-Soviet world have shown that they do, and it does. Urban spaces in the former USSR have inherited a highly specific, if often conflicted, attitude to art in the public space, which in itself may be partially responsible for Ukraine’s desire to remove remaining reminders of the past from its streets. In many ways, it is unsurprising that urban visual iconography is constantly adapting. For it is not only symbolic to reject the past, either by reappropriating its methods or trying to destroy it completely; it is necessary to create distance for processing the past and separating it from the present. Whilst the long-term outcome in Belarus is still uncertain, recent developments already hint at a determination to take back the public space. Nevertheless, even in a country like Ukraine, which has already taken drastic action to eliminate overt references to Communism, a clean break with the past is never simple, as society cannot help but react to what came before.