Heritage Speakers — Linguistic Remnants of Biculturalism

Anna Anossovitch

The concept of ‘heritage speakers’ has formalised the effect wider cultural and global developments have had on a generation which is uniquely linked not by a trait, but by a shared experience. Heritage speaker populations started confidently entering the linguistic literature about two decades ago, characterised by their circumstantial bilingualism — one language spoken in the home, whilst another is dominant in the greater social context. An ingrained linguistic consequence of migration, it most commonly involves incomplete language acquisition or attrition of the heritage language, i.e. the language spoken in the home, while also intertwining with the navigation of a bicultural environment.

From a linguistic viewpoint, it’s uniquely significant that such specific social ramifications have fielded an academically widespread identifying term. But do not fret, dear reader, for we will not be dissecting any linguistically dense journal publications today. What is interesting is the commonalities between so-called 2nd generation immigrants, and why there is a pattern of incomplete acquisition and attrition among them — or among *us*, I should say since I, for full disclosure, fall under this category myself.

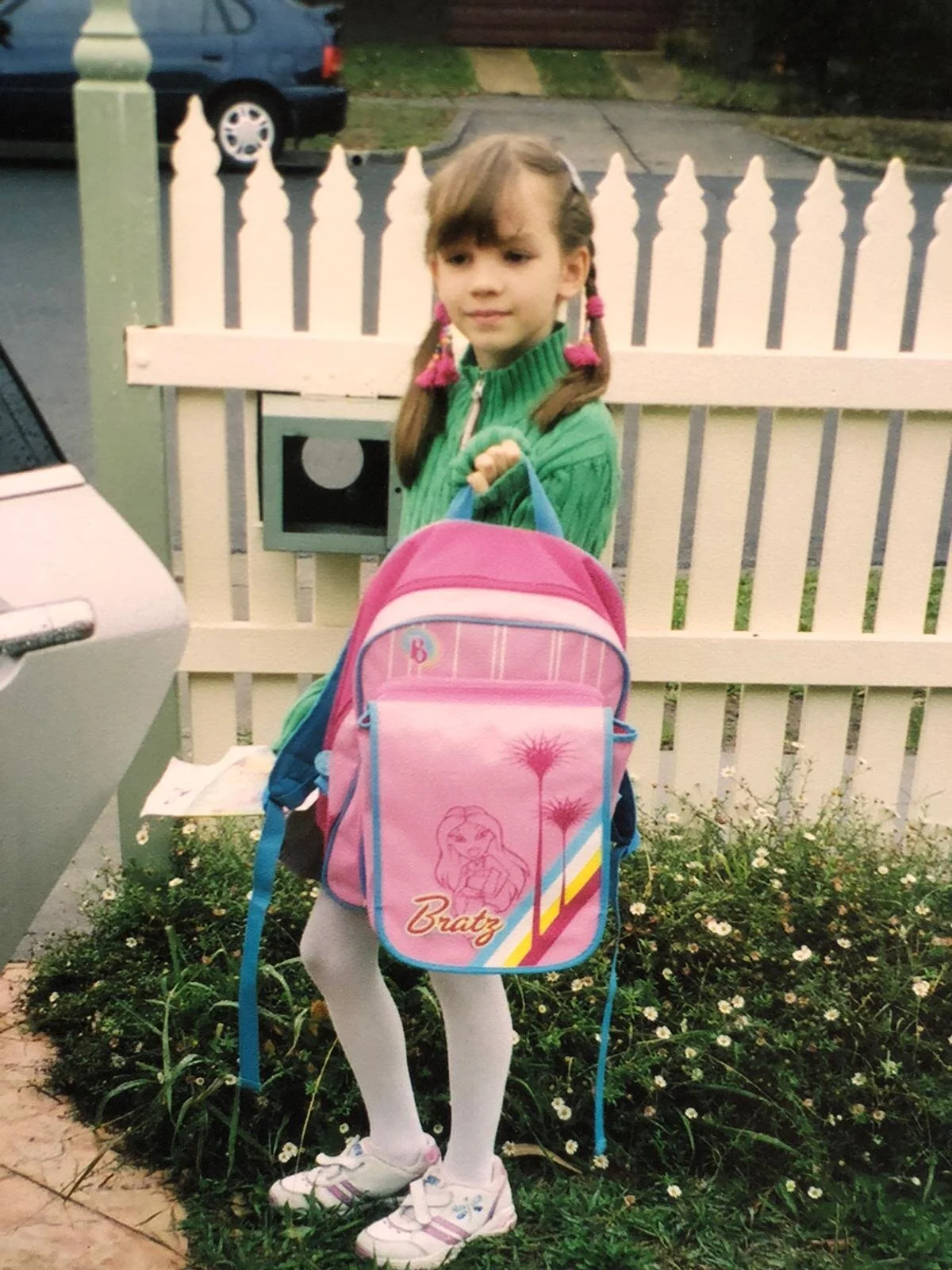

A childhood photo of myself, unenthusiastic about the impending hours I was about to spend in a Sunday language school

I’m not qualified to talk on behalf of anyone else, so I will root my descriptions of this social phenomenon in my own background. I hope to illuminate the experiences which typically unite heritage speakers across cultures and across borders. A 1st generation immigrant is someone who departs the country where previous generations of their family have resided, and settles in a new one, typically emigrating from a developing country to a more developed one. In my case that would be my parents, who immigrated to Australia from Russia, where their families still currently reside. A 2nd generation immigrant is the child of 1st generation immigrants, either born in or relocated to the new country at a very early age. That would be me, who was born in Australia to my Russian parents.

Another term sometimes used in such situations is ‘third culture kids’, referring to the two different cultures inside and outside of the home, the ‘third culture’ being an amalgamation of the two. In my opinion, this isn’t a faithful characterisation of bicultural upbringing because cultural identity is still primarily derived from its two major influences. Whilst there are cases where an immigrant community has truly established a third culture, most experiences with biculturalism don’t centre around or even involve a supposed third culture.

For this reason I prefer to talk about ‘2nd generationers’, or 2nd gen-ers for short. The extent to which 2nd gen-ers associate with their heritage culture and the dominant culture varies depending on a myriad of factors, impacting how strongly they identify with the bicultural experience. Precedent and the greater social landscape also play a role, where connecting with other 2nd gen-ers can help bridge the cultural gap and provide a blueprint of sorts for navigating such a dynamic. I grew up around the term ‘ABC’, which stands for Australian Born Chinese (also used in the U.S. as American Born Chinese), normalising and carving out an identifier for 2nd gen-ers. Curiously, ABC has scope to be read as “Australian; born Chinese” or “Australian-born Chinese”, but the interpretation of slang lies solely in the hands of the communities who use it.

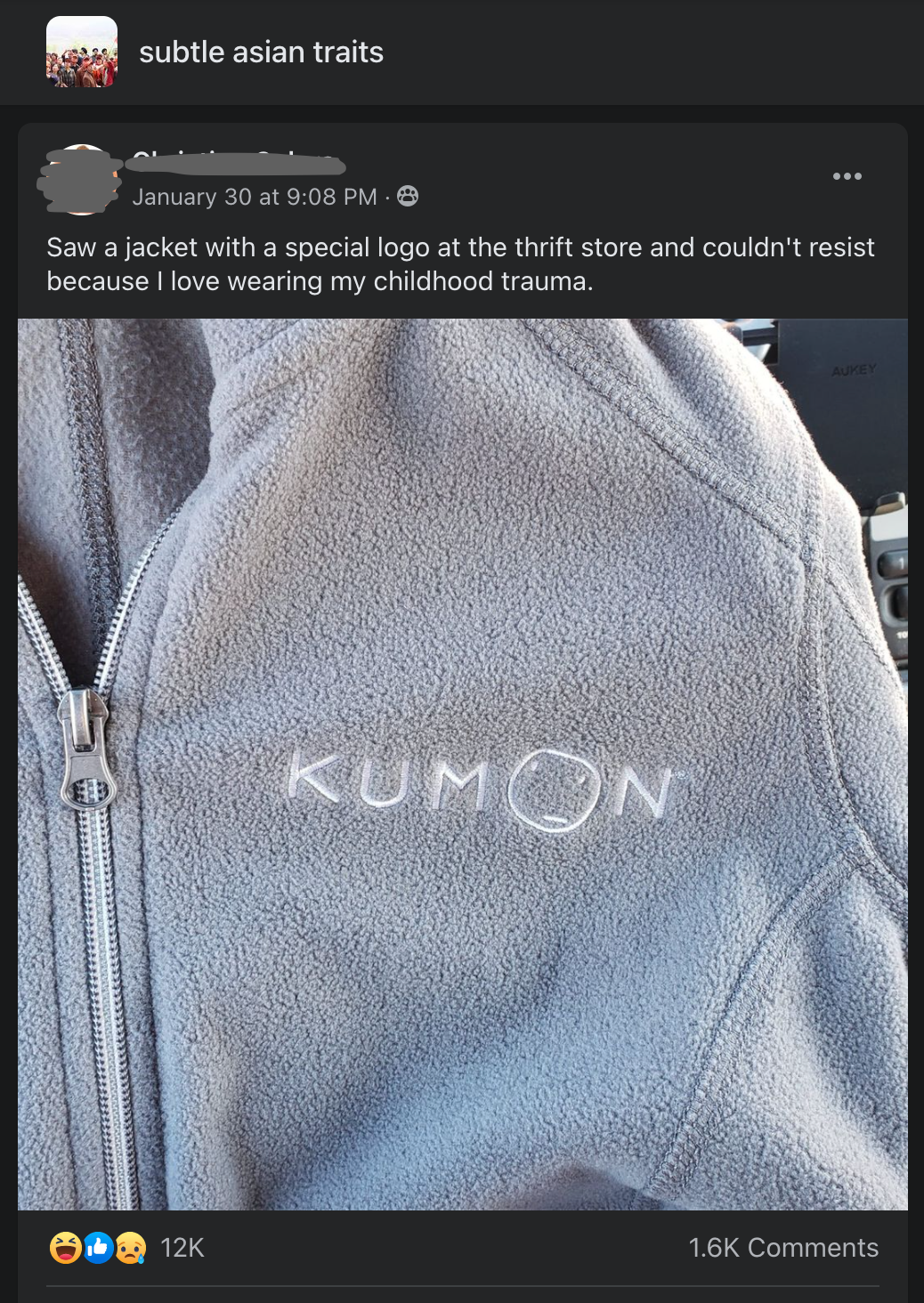

A typical SAT post, here referencing Kumon — a demanding after-school tutoring program popular with immigrant parents

One of those communities is the global phenomenon Subtle Asian Traits (SAT), which was originally created by fellow 2nd gen-ers in my home city of Melbourne. A resulting derivative is Subtle Curry Traits, but before its creation, many South Asian 2nd gen-ers enthusiastically engaged with the primarily East Asian themed content on the SAT forum. Not because there are necessarily a host of similarities between South and East Asian culture, but because coming of age in a bicultural environment is an overwhelmingly unifying experience. The identity and integration issues at the core of 2nd gen discourse is what anchors the relatability, allowing descendants of varying heritages to form a bond. Filipino, Australian, Japanese and English natives would typically have little to build a shared identity on, but despite them being markedly different countries on the world stage, my Filipino-Australian friend finds SAT to be just as relevant of a community as my Japanese-British friend. I, too, have found solace in many of the ideas touched on in SAT.

At this point I need to flag the intersecting role of ‘race’ in this discussion. I use the term in quotation marks because the concept of race is largely dominated via a white lens, serving as a crude social reconstruction of ethnicity. The societal significance and categorical perception of race also varies wildly across the West. For instance, the historical assimilation of Turkish Gastarbeiter in Germany results in a starkly different public perception of Turkish culture than, say, in the U.S., where the ideation of Middle Eastern heritage has been hounded by the War on Terror and Islamophobia. Racial discrimination undoubtedly holds a critical role in 2nd gen discourse, but I would argue that the bicultural experience is not underlyingly rooted in facing discrimination. Not only because racial relations are critically different between socio-political contexts, but because the white delimitation of race consistently benefits the white-passing, regardless of ethnicity. This is to say that, apart from the Slavic sign-post that is my surname, I consistently benefit from the privilege of being white and therefore native-passing. In the same vein, the more white physical features one has, the more freely one can dissociate from their biculturalism, avoiding the likes of

“...but where are you from from?”

Relating the essence of biculturalism to racial discrimination thrusts the identity disproportionately upon those who are visually judged to be foreign, also resulting in monoculturally-identifying PoC being falsely assumed to be 2nd gen-ers.

The core of identity struggles common with 2nd generationers lies in the purgatory between the two contrasting cultural environments. Growing up biculturally involves juggling the two sides — being too westernised to fully identify with the heritage culture, whilst being too nonconforming to fully integrate into the socially dominant culture. The key clash occurs when one’s priorities shift from their family unit to their peers. All of a sudden, fitting in is the be-all end-all, and the different home culture must be suppressed in order to maximise belonging. It’s no longer just annoyance at strict parents or weekend language school, it’s true disdain for the socially divergent part of yourself; internalised xenophobia.

The irony of bicultural identity struggles is the perception of monocultural peers as the stable ideal. One of the pillars of adolescence is insecurity, and it’s easy for 2nd gen-ers to forget that even though it might not include the same bicultural dimension, everyone else experiences identity struggles too. Yet the compulsive desire to fit in can cause a seed of resentment to grow — “Why can’t we just eat normal food?”, “Why can’t we celebrate the same holidays as my friends?”…

“Why can’t we just speak English?”

And here, I posit, lies the main contributor to incomplete heritage language acquisition and its attrition. Communication is inherently wrapped up in language, and if a bicultural child chooses to ostracise their heritage as a social self-defense mechanism, it can very quickly halt their language development in its tracks, or cause it to gradually fade from memory as it falls out of use. The ease of early language acquisition construes one’s mother tongue as indestructible. ‘Mother tongue’, referring to the language passed to you from your mother, is typically interchangeable with ‘native tongue’ or ‘first language’, but many 2nd gen-ers come to a sudden realisation at some point that their mother tongue is no longer their native language. Lost language abilities force self-reflection by clearly signifying the greater cultural disconnection, and ultimately alienation from one’s own heritage.

This realisation may trigger feelings of regret, indifference, or even relief. The bicultural experience has different outcomes for different people, reflecting the choices made in the struggle with identity and finding one’s place in the world. So yes, I’m sad I lost my mother tongue. But if I never confronted my resentment, I may never have recovered that part of myself, and made peace with my origins as well as the decisions I had made along the way.

This article is dedicated to all my fellow heritage speakers out there, and, of course, to my mum and dad, who gave me my heritage in the first place.