The ‘Righteous Thief’ Liao Tianding, and How His Legacy is Shaping a New Generation of Taiwanese Resistance

In the face of growing political uncertainty, Taiwan has turned to a familiar character from its folklore as a spiritual figurehead for the pro-independence movement. Why?

Taiwan has suffered relentlessly at the hands of war, tyranny, and imperialism over the past century. Until 1945, its people were deprived of their most basic civil liberties, treated as second-class citizens by unforgiving Japanese occupiers. Now, with the atrocities witnessed under the White Terror, a period of martial law between 1947 and 1987, still fresh in the people’s memory, Taiwan faces the looming threat of invasion from China. Against this turbulent geopolitical backdrop, Taiwanese people find themselves looking for reassurance. However, faith in mainstream politics’ ability to withstand increasingly frequent acts of aggression from Beijing appears to be wearing thin. President Tsai Ing-wen has seen her support eroded since her election in 2016, most alarmingly among Taiwan’s ardently pro-independence youth; according to a 2021 poll, her approval rate among voters aged between 20 and 24 has plummeted from 93% to 47%, a decline steeper than that among any other age group.

Statue of Liao Tianding in Taiwan (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Thus, in the absence of decisive leadership, folklore has emerged a source of hope. This is nothing new: throughout the bleakest chapters of Taiwan’s modern history, dissidents have sought guidance in the stories of legendary figure, Liao Tianding. Born in 1883, twelve years before Japanese occupation, into an impoverished village outside modern-day Taichung (Taizhong), Liao worked odd jobs after suffering the loss of his father in his adolescence. As he entered adulthood, he became the subject of prolonged investigation for the armed robbery and vandalism of Japanese colonial overlords’ property. As such, he was forced into hiding in a remote mountain cave, where he was captured and killed in 1926. His tomb has since been memorialised as a temple in New Taipei City, where frequenters worship him as a quasi-deity for his service to the Taiwanese people.

Liao Tianding Temple in New Taipei City (Photo credit: Liam Elliott Brady)

Temple awning decorated with dragons and tutelary figures (Photo credit: Liam Elliott Brady)

However, it was not until the White Terror that Liao was reimagined as a symbol of the subversive pro-democracy movement. Pirate radio host, Wu Letian, told tales of Taiwan’s ‘righteous thief’ on air, his fight against oppression resonating with a population living under suffocating martial law and inescapable fear of arrest. Wu’s efforts to rouse civil unrest have since been immortalised in Adiong Lu’s documentary Once Upon a Time When Robinhood Grew Old, and have come to represent the struggle against tyranny in Taiwan.

It therefore comes as little surprise that the legend of Liao Tianding has been resuscitated by those skeptical of the mainland’s expansionist designs. This revival is, in part, owing to the success of an independently released computer game, The Legend of Liao Tianding, in 2021. Discourse on PPT (a social media platform popular among politically aware youth) is replete with satirical references to the game and the legend surrounding it. And, while the lion’s share of this discourse centres around trivialities such as graphics, gameplay and walkthroughs, discussion of Liao’s life is invariably accompanied by glaring political undercurrents.

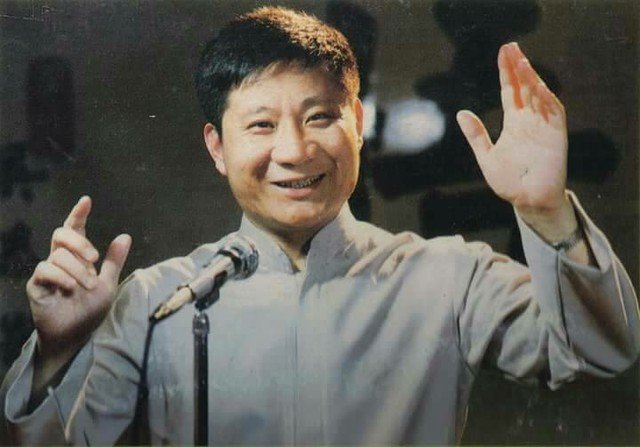

Taiwanese pirate radio host, Wu Letian, famous for his performance of ‘The Legend of the Legendary Liao Tianding’ (Source: Facebook)

As one user laments the inaction of Taiwanese politicians (or “imperial subjects”) in the face of Chinese aggression, they question whether Liao would have fled the island in anger were he alive today. Other users invoke Liao’s legend to illustrate less sardonic takes on Taiwan’s situation. The parent of a six-year-old daughter, for instance, talks of the game’s utility as a tool to instil pride amidst a crisis of national identity. A theme that appears to underpin all commentary on Liao’s enduring relevance is his ability to lead against mightier opponents. In this light, one user argues that Liao would have proven to be a more formidable leader against Mao Zedong than Chiang Kai-shek.

As Taiwan approaches its folklore with renewed curiosity, the legend of Liao Tianding has adopted a central role in the rhetoric of pro-independence activists online. While this nostalgia is hardy unprecedented, it appears to have reinvigorated Taiwan’s disenchanted youth. Disillusioned by Tsai’s supposed inability to keep the mainland at bay, one user bemoans her as the “goddess of the one China policy.” Another submits a more hopeful response:

“Look to Liao Tianding: the godfather of Taiwanese independence.”