Egg Tarts (ft. the British Empire) [Cantonese Remix]

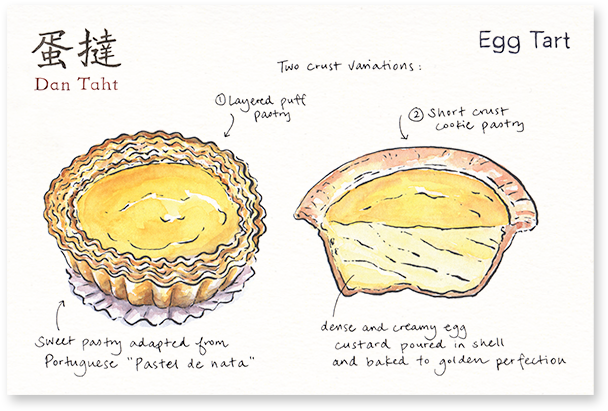

Illustration of the anatomy of a Cantonese egg tart. (Image credits: PNGkey.com.)

The egg tart is one of Hong Kong’s cultural trademarks, and a staple of Cantonese local cuisine. However, this sweet treat is not wholly unique to the city, and has its origins halfway across the world. Stephanie Jat delves into the history of the dish that marked her childhood, and details the remarkable journey which brought egg tarts to the table of the masses in Hong Kong.

If you were to ask me for my fondest childhood memory, I would probably think back to my primary school years spent in the hustle and bustle of Hong Kong. Its skyscrapers and scattered colonial infrastructure give way too dense, squat cement blocks threaded with the fragrance of street food waiting in hawkers’ stalls, wafting out of open bakery doors.

Every Monday, my mum would pick me up from school, a lilac cake box in one hand. To this day I am still convinced that snacks are the best way to ward off that Monday blues. Inside that sacred box, would be six 蛋挞 (Mandarin: dàntǎ; Cantonese: daahn6 tāat7). Daahn tāat are more referred to as ‘egg tarts’ in English, and consist of a sweet and creamy egg filling encased by a puff pastry cup.

An egg tart (left) and coconut tart (right) with a hot cup of Ovaltine served in a cha chaan teng. (Image credits: Wikimedia Commons.)

They usually fit in the palm of your hand, perfect for doubling (or quadrupling) up, or pairing with another sweet treat.

Egg tarts can be found in bakeries, often bought in half-dozens, or ordered on their own at a cha chaan teng - Hong Kong-style cafe which serves anything from French toast to baked tomato sauce pork chop rice.

Products featuring characteristic Cantonese food are almost definitely going to include egg tarts, such as this artist on Redbubble from Hong Kong. Clearly, egg tarts are at the heart of Cantonese cuisine and culture, but you might be surprised to find out that just like ketchup - an Americanisation of 茄汁 (Cantonese: ke2 zap1) - egg tarts did not originate from the culture they are most well-known for.

Egg tarts have a very similar-looking cousin, the Macanese egg tart, local to Macau, 60km west of Hong Kong. These are usually made of the same sweet egg filling but with filo pastry instead, and the tops are sprinkled with cinnamon and flambeed. These were inspired by the Portuguese pastéis de nata and first made by British pharmacist Lord Andrew Stowe, whose recipe skyrocketed in popularity after it was sold to KFC in 1999.

You may be tempted to assume that the Cantonese egg tart, almost compulsory at the end of a satisfying dim-sum Sunday brunch, is also related to the Portuguese pastel.

Not quite.

As it turns out, the Cantonese egg tart’s ancestor originated in Britain, as early as the 1400s – in a 1450 cookbook, Two 15th Century Cookbooks, the second oldest known English language cookbook. (Yes, this makes it a colonial relic, but they taste so good I’m beyond complaining.)

In Britain, however, they started off as custard tarts. Marc Meltonville is a food historian who worked extensively in the Hampton Court Palace kitchens to explore their usage and to research and recreate historical (specifically, Tudor) foods. In an interview, Meltonville reveals that British custard tarts at the time were made with shortcrust pastry, and the filling had “cream, eggs and a sprinkling of sugar”, which we would expect, but also “parsley, dates, prunes and bone marrow”. The marrow is to add creaminess, the dates to complement the “sprinkling of sugar”.

In the 17th century, the global climate interval, the “Little Ice Age”, began to affect Britain. Mean annual temperatures across the Northern hemisphere dropped by 0.6ºC, and people resorted to comfort food for keeping warm. This is the period when the custard tart established itself as a recipe of egg, custard, milk and sugar.

Fast forward to the 19th century, as Britain’s imperial power expanded, traders and government officials dispersed to Southeast China. It’s therefore no surprise that those who could afford to, would bring their chefs with them, so as to have the luxury of eating traditional British dishes in the heart of Southeast China’s damp, tropical climate.

British chefs often worked alongside Cantonese ones in the kitchens of the foreign concession areas of Southeast China. The latter would watch their British counterparts as they prepared these tarts, and in turn, learned how to master the recipe themselves, except for adding a slight twist of their own.

Custard was a foreign, unfamiliar product that was expensive and hard to come by, so they replaced it with only egg, sugar and milk. Instead of the shortcrust pastry, they used puff pastry custom to Cantonese dim sum, made with inexpensive pork lard rather than butter. In the 1930s, flower-shaped moulds were introduced, and these were preferred over the original oval shape to give the tarts a more appealing aesthetic too.

By the 1940s, wealthy Cantonese people moved to Hong Kong, bringing this new recipe with them. However, egg tarts were still restricted to high-end Western restaurants, served as a luxurious delicacy.

It wasn’t until after the Second World War, when British hold on Hong Kong loosened, and more and more local brands began to gain popularity and formal recognition from the government, that affordable local restaurants (cha chaan teng) made the egg tart available to the public too.

A cha chaan teng, an affordable local café which was popularised in the 1940s. (Image credits: WJN.)

So, what has happened since?

If you walk down any of the packed streets nowadays, you’d still be able to smell freshly-baked egg tarts in the display windows of cha chaan teng, with a queue of eager customers endeavouring to get one before they go cold. They’re available from local bakeries, and as a popular dessert item when you have dim sum.

The shortcrust pastry Cantonese egg tart is now almost universally available in Hong Kong, since they are now cheaper and faster to make, although some locals may see these as “less authentic”. Although I would argue that the traditional recipe is still the crowd favourite, egg tarts have also adapted to the multicultural landscape of the city.

Now, there are egg tarts in all sorts of flavours: matcha, coconut, chocolate, durian, lemon. You can even find recipes for milk tea- or pandan- and ube-flavoured ones!

Different flavours of egg tarts in a shop window, including Hokkaido 3.6 milk (left, white), original (middle, yellow), and durian (right, beige). (Image credits: Wikimedia Commons.)

The latest trend has actually been a Japanese-inspired Hokkaido milk-flavoured one I personally am dying to try.

The evolution of the egg tart. (Image credits: Wikimedia Commons.)

Egg tarts are unarguably a staple of Cantonese cuisine, and consequently have become a symbol of the colourful culture embedded in the history of Hong Kong. I find it fascinating that a palm-sized sweet bake, whether it’s the Cantonese egg tart, the Macanese egg tart, or the Taiwanese variation, can hold the story of a city, telling us about the intercultural contact which led to its invention.