Tongue Tied IV - Sámi on the Brink

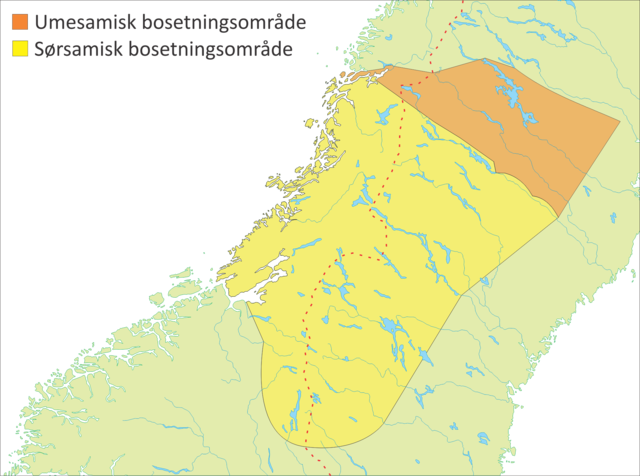

Map of Trøndelag and Nordland in Norway, and Jämtland and Västerbotten in Sweden; showing the traditional areas of the Southern sami and the Ume sami in Norway and Sweden. From Tjaalehtjimmie (Dunfjeld, 2006). Image and description credits: Wikimedia Commons.

‘Tongue Tied’ is a short tour through Europe via some of its most at-risk languages. In a series of four articles, Columnist Kieran McGreevy will examine four languages from across the corners of Europe, with the aim of showing what has led these languages to the brink of extinction (and sometimes back), by untying the history of the people, the linguistics of the language itself, and the efforts being made to keep these tongues alive. In the last instalment, Kieran looks at Umi Sámi, a descendent of Uralic language used along the north of Sweden, and how it differs from Scandinavian languuages.

Fact File

Name: Ume Sámi

Language family, subfamily: Uralic, (Western) Sámi

No. of speakers: 10-20

Geographical spread: Along the Ume River in Northern Sweden, and formerly in Norway

History

Thanks to strides made in linguistic and genetic research, the Sámi people can be traced back to somewhere very far from their homes today. Their languages are believed to originate from the regions along the upper and middle Volga, a river today in Russia towards central Asia. More famous Uralic siblings are Finnish and Hungarian in the Finnic and Ugric branches respectively. From here, they are expected to have moved northwest towards their current home in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, ending up in the Finnish Lakeland around 1600 and 1500 BC, and finally in their present location after the beginning of the Common Era. The existence of these peoples was even acknowledged by the Romans as far back as 98 C.E., in a document written by Roman historian Tacitus in his De Origine et situ Germanorum, a text on tribes in Germania, where the ‘Fenni’ (Sámi) resided at the time.

Despite migrating to Scandinavia at similar times, Norsemen and Sámi had very little contact, despite what may be expected. For centuries Sámi people lived primarily in inland (northern Fenoscandia) and Scandinavians (the Germanic peoples that are generally referred to by this title) in the south, gradually colonising the Norwegian coast as well. The quintessentially Sámi way of life that one may imagine – reindeer-herding nomadism, settling in tents or turf huts in units of several families and supporting themselves where necessary with hunting and fishing – only began to be threatened to great extent in the 18th century by Swedish colonialists.

Ume Sámi speakers, however, lived a slightly different life to the rest of their cousins in Scandinavia, and thus suffered the effects of colonialism in a different way. They lived in forests, and in this culture, they were reliant on more small-scale reindeer herding, which did not require a fully nomadic lifestyle. This made them adapt more readily to the permanent settlement encouraged by the Swedes and thus be assimilated into Swedish society more easily.

A shift in Swedish politics began, however, with a movement known as Lapp shall remain a Lapp (Swedish: lapp‑skall‑vara‑lapp). Using Lapp to describe the Sámi people became derogatory. This movement sought to limit this increasing assimilation, separating Sámi people from Swedish society and education by encouraging a semi-nomadic lifestyle based on large-scale reindeer husbandry. The forest Sámi that included speakers of Ume Sámi, however, had never had this lifestyle, preferring smaller herds, and thus had undergone greater assimilation and were less inclined to adopt a new lifestyle, like those of their mountain kin. As such, the Ume Sámi were largely ignored in politics of the time and onward, and the number of native speakers continued to rapidly decline to the incredibly low number it has reached today.

Features

Of all the languages discussed in this column, Ume Sámi is the furthest away from English, being the only non-Indo-European European language addressed (this is not an oxymoron, I promise). It is worth noting that most examples given here, because of the lack of documentation of Ume Sámi, have come from Pite Sami, a closely related Northwestern Sámi language. Here are some of its most unusual features (compared to European langauges):

Anyone who has interacted with any primary-level English education recently, will note how early on kids are taught to form the plural of words from the singular, which, despite English’s many irregularities, is often a simple task – we add -s: dog vs. dogs, table vs. tables. But Ume Sámi, like many other languages in its family and around the world, makes a third distinction, one specifically to denote a ‘dual’ number, meaning two.

Måj ma lin båhtam – ‘We (two) who had come’

Although noun cases are a part of many Indo-European languages, they are found in Uralic languages too. These are often endings added to nouns to express certain meanings, such as its location, or whether it is the subject or an object of an action. Students of Latin or German for example might recognise such terms as the nominative, accusative or genitive cases, all of which Ume Sámi has too, but it actually has five more. Two of these cases, the illative and inessive, make a distinction often lost with English’s use of a preposition to fulfil the same function, that being ‘in’. This distinction is best shown by instead using ‘into’ to describe illative, and ‘inside’ to express inessive: one denotes a movement into a place, the other denotes the existence inside it.

Muhten båtsoj ij bade gärrdáj – ‘Some reindeer don’t come into the corral’

Vággen Sálvojåhka’l – ‘Sálvo Creek is in the valley’

Below, the -j on the end of gärrdáj expresses the meaning of ‘into’, as -n captures the meaning of “inside” in the word vággen. The copular verb meaning ‘is’ in the second sentence is also not a totally separate word, instead -l added onto the subject after an apostrophe in Sálvojåhka’l.

This next feature is finally one that is uncommon but somewhat shared by English, although not to the same extent, and can be seen in one of the last examples. While most Indo-European languages have a negation particle, a word that is unchangeable and attached to a verb to express a negative sentence – I would not go home. Sámi languages, like English in simple past and present tenses, has a negative verb, one that conjugates to reflect who it is referring to, like other verbs do in these languages. Unlike English (which has don’t and its other forms), this inflects to show the tense, mood, person and number of the subject referring to in Ume Sámi.

Muvne ij lä aktak vuopta – ‘I don’t have any hair (lit. on me isn’t a single hair)’

While, as stated, the examples thus far have been of Pite Sámi, which has more readily accessible examples available, ij is identical in Ume Sámi.

Ume Sámi makes three vowel quantity distinctions: There is a difference between short, long and overlong vowels. This is because of a grammatical process called consonant gradation, which is too complex to do justice in this article. As Ume Sámi is the only among its group to still have this feature, the examples here are taken from Northern Sámi instead of Pite Sámi.

(with the vowel preceding the -s- going from longest to shortest)

Guos’si vs. guossit vs. viesut – ‘guest’ vs. ‘guests’ vs. ‘houses’

Resistance

It is not hard to reach a conclusion as to why any former speakers of the Ume Sámi branch of the language subfamily have disappeared from Norway. Their religion prior to Christian colonialism was condemned as witchcraft and their ritual drums were burnt, even if thankfully some of these items can still be found in museums. Until World War II children were not even allowed to be taught in a Sámi language, with the entire curriculum being obligatorily taught in Norwegian. The other Sámi peoples that remained finally saw intervention on behalf of the Racial Discrimination Committee of the United Nations in 2011, which made recommendations for the improvement of its treatment of minority communities. In Norway, Sámi people now have their own parliament and rights to ancestral lands, in large part to huge amounts of activism work done by these communities.

It is perhaps of no surprise that the Ume Sámi people have managed to scrape by in Sweden, given its marginally better treatment of these groups. A Sámi parliament in Sweden came to be in 1993, after the formation of Sámi associations after political struggles in the 50s, which sought to foster a pan-Sámi culture across groups across all of Fennoscandia, promoting it as a culture with many shared traits set apart from mainstream society. However, with the languages only being taught in schools from 1962, resulting in a lack of literacy and many members of younger generations choosing professions away from the traditional reindeer herding and living in more modern housing, it is difficult to keep the minority languages of this language family alive.

Today, the language only survives natively in 10-20 people who are no younger than 60 years old, which is why efforts to document and support the continuation of languages like Ume Sámi is so important. Ume Sámi thus serves both as a warning of what can happen to a language and community not given sufficient support from neighbours, nations and world organisations, but also a beacon of hope that even in the farthest reaches of Europe and in the most hostile environments (politically, although this statement is apt for its geographical environment too), outside pressures can continue to be resisted.

As all Sámi languages are experiencing some level of threat that may result in their extinction, here are some resources for not just Ume Sámi, but other related languages too.

https://youtu.be/_qpDdTr43vI – Songs in Ume Sámi

https://youtu.be/GU74jfJl6Ug – Máddji is a Norwegian Sámi singer, and her album Dobbelis – ‘Beyond’ – is largely in Northern Sámi. Other artists include minimalist folk-rock singer Mari Boine, from Norway, and Finnish folk metal band Sháman.

https://youtu.be/f79LXi11d_E – A quick crash course to Northern Sámi, the most widely spoken

https://youtu.be/hd5MB1W5Rg8 – Northern Sámi spoken

https://youtu.be/2IzpOFfd4Zs – Kildin Sámi, an East Sámi language, spoken

https://youtu.be/-8ZNc02x-U0 – Lule Sámi, a Northwestern language alike to Pite Sámi, spoken