What’s App in Italian Linguistics I - From WhatsApp to Linguistic Research

By Rebecca Gatti

The project logo, designed by Federica Buscaglia

We can certainly get a lot about a culture from how people speak. But now, with the use of social media and online chats, we can widen our knowledge focusing as well on how people “write”. If you want to follow our columnist Rebecca Gatti in this journey through Italian “digital” linguistics, buckle up and get ready to find out how Italians really speak.

In this instalment, Rebecca will introduce you to an innovative project aimed to collect data from Whatsapp chats.

In 2020, during lockdown, a group of students from the University of Pavia, a little town near Milano, looked themselves in the eyes through their computer screens and had an idea for an online corpus that had never been created before in Italy.

Following the classes of Ilaria Fiorentini, Sociolinguistics Professor, they realised that we were missing data from the most used form of communication: WhatsApp. That’s how, with Fiorentini as the lead, they started collecting data from their own conversations with family, friends, university’s colleagues, doctor’s secretaries for medical appointments, whatever they found in their WhatsApp backups.

This has led to the WhAP! project (not yet released online) with over 58 chats and 22,000 words to which we’re contributing every day with more data. The conversations are anonymized, and everyone needs to provide a consent form before getting information from the chat with someone.

This project will be very useful for linguistics research since people can investigate different phenomena happening online, and that’s exactly what I’m here to do.

Since the first social media appeared in our everyday life, we have had to stop considering the binary division between written and spoken language: online, millions of people have taken back the written form, with a huge expressivity that tends to imitate oral communication.

As we can understand, this input of oral forms in the written (even if it would be more correct to speak about ‘digitised’, as it implies a lot of differences from the physical act of writing), has led to a ‘desacralization’ of it. So, we can easily understand that one of the most interesting features of online language is the presence of pragmatics dynamics and how they are processed and accepted in the digital communication system. Specifically, discourse markers are over-used in Italian chats and that’s because you could easily spot hundreds of them in every Italian oral speech.

The project began during sociolinguistics classes, when Professor Ilaria Fiorentini came up with the idea of building the first corpus of online WhatsApp conversations. As two of the student founders (Barbara Mazzotta and Alessandro Valeri) like to point out, it’s a special project that was born during Covid time, when online chats had increased a lot, bringing in people that hadn’t done it before to chat as well.

We hope we can soon go online, to help increase the opportunities of linguistics’ research, even with the small amount of data that we have. This is also a huge opportunity for the students that are working on it, being a great topic for scientific articles, dissertations and much more. We started a fundraiser online at the Universitiamo website (a fundraising association from University of Pavia that helps different projects in raising money), and we organise a lot of events in Italy to try and get more well-known.

Finally, some examples

Discourse markers are particularly interesting: they are particles of the discourse that we use for different pragmatic reasons. They don’t belong to a single morphological class, but they are connected to each other by their purpose. Discourse markers (DMs) can easily be found in everyday speech, and since online communication has mingled so much with oral communication, we can now see them in almost every text we analyse.

Something fascinating about this category is that we usually find a transfer of meaning: to give you some examples we’re going to quickly see two categories of discourse markers, having a look at the research from two Pavia’s students (Daniela Santoro for vabbè and Federica Fiore for senti), that we’re going to analyse better in the next article. Right now I’m going to present just the primary functions of these DMs.

The interesting thing about these two particles is that in one case we find a slight semantic shift, and the other one that we can clearly see being an interjection.

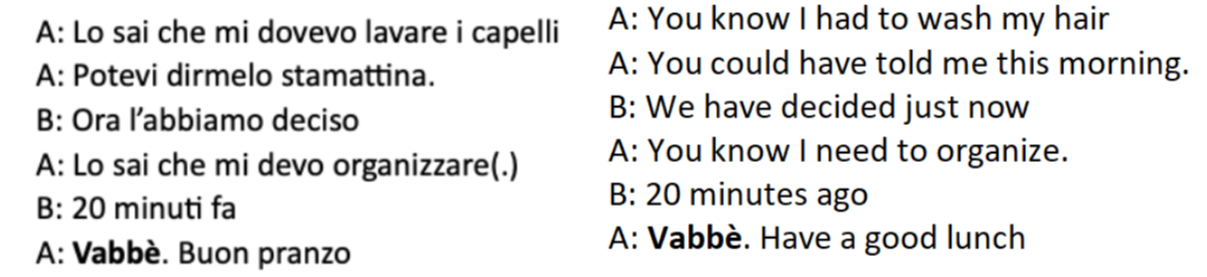

Vabbè

As we said, it’s “an interjection, a univerbate form for va bene (‘all good’), with phonotactic doubling. It’s often found in the end of sentences, as exclamation for rush or impatience or annoyance.”(from Daniela Santoro).

As we can see, ‘vabbè’ here highlights the irritation of A towards B but it has many more meanings, as we will study in the future.

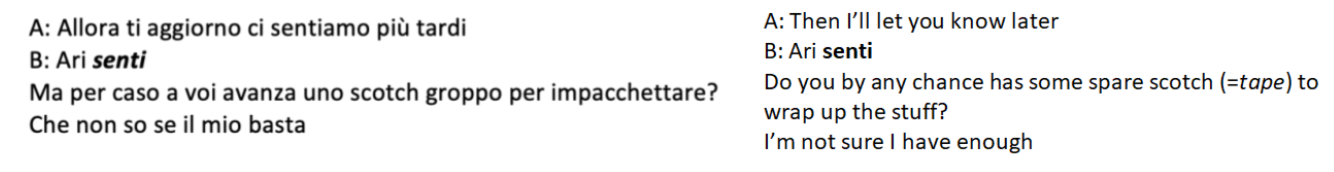

Senti

We usually find ‘senti’ at the beginning of the sentences, “to draw the interlocutor’s attention, or express hesitation and getting time to collect ideas, with its function being to structure the speech, other than a marked way to start the conversation shift”. (from Federica Fiore)

The difference from ‘vabbè’ is that ‘senti’ has been desemantised, free from its original meaning (“listen”) and frozen only on its multiple pragmatic functions. This happens as well with words like ascolta (“hear me out”), guarda (“look”), vediamo (“we’ll see/let’s see”)

Here is its main function:

I hope this little sample of what working with Italian chat can offer has drawn you in enough to keep on following!

If you have some specific phenomenon that you would like to investigate and learn something more about it, let me know through my email rg712@cam.ac.uk.

Alla prossima!