La troisième fois sera la bonne?

Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear (Image Credits: Jérémy-Günther-Heinz Jähnick, GNU FDL V 1.2 via WikiMedia Commons)

In the weeks before the 2019 UK general election, a strange intoxication befell many supporters of the Labour Party. They believed, sincerely, that the campaign would end in a hung parliament, or maybe even a Labour government. This was in spite of enormous and consistent poll leads for the Conservatives. For the sadly deluded, the 12th of December was to be an ice bath on a summer’s day. Why had so many convinced themselves, in the face of all reasonable evidence, that a Tory landslide was impossible? Because of what happened before.

In 2017, people had been expecting a coronation for Theresa May, but the election denied her a majority, a result that upended months of conventional “wisdom”. The reality is that the data had shown it coming – YouGov’s MRP model had been predicting a Tory minority for weeks, and anyone could see May was a weak public speaker with little charisma. People then took the wrong lesson from 2017 – the polls had been (largely) right, and expectations were wrong, not vice versa. The right lesson of 2017 was that the Tories were in a strong position for the next election; after a terrible campaign, they had still managed to win their largest share of the vote in 25 years, and were still the Government. There was no rational reason to underestimate them at the next ballot.

This is precisely the mistake many risk making with Marine Le Pen.

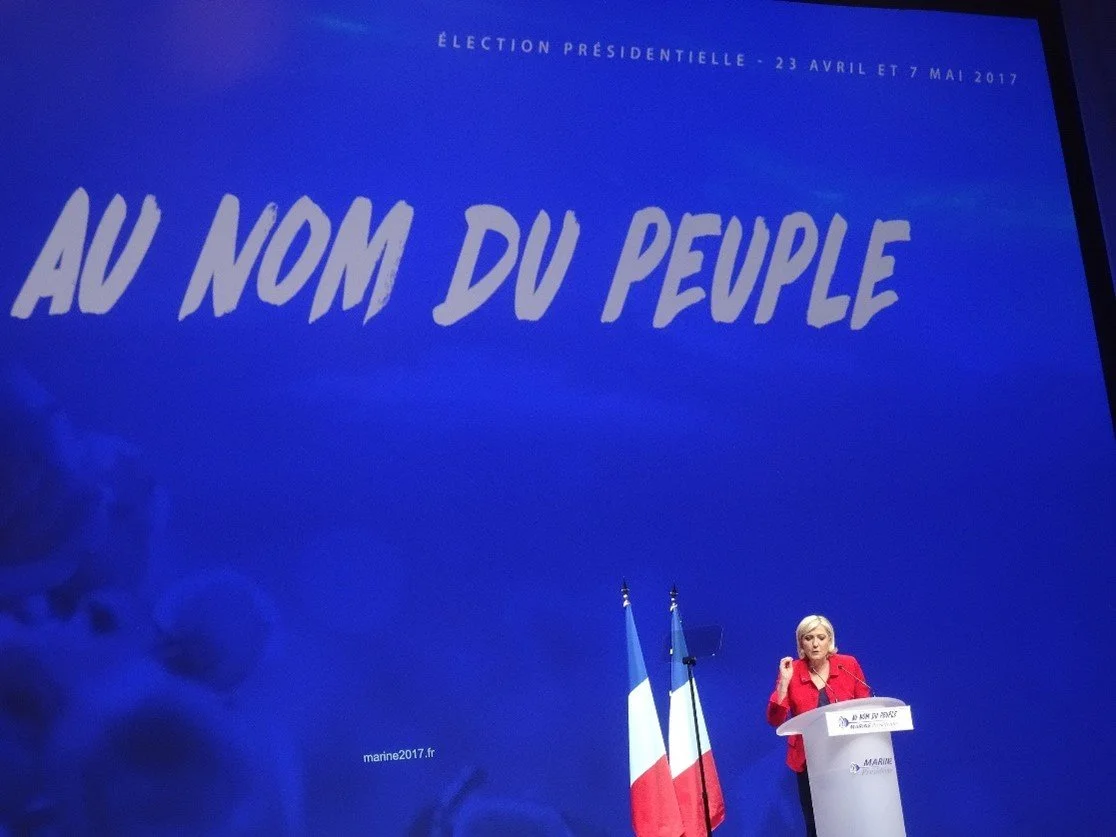

In the 2017 French presidential election, Le Pen lost by a colossal two-thirds margin. It would be quite understandable to assume this would be her political demise, but her reaction to the defeat illustrates why she mustn’t be written off. She did not grieve or strop, she did not (like some of similar political persuasion) try to have the results overturned. She took her loss seriously and devoted herself to studying why and how she failed. Le Pen rebranded her party, ditching the name her father gave it, having already ditched her father – a man whose virulent xenophobia still heavily taints her name. Unpopular policies, such as an exit from the euro, were dropped. Marine Le Pen spent five years crafting the conditions for victory in 2022; by the summer of 2021, her entry to the second round seemed secure.

Then arrived the candidacy of Eric Zemmour, a charismatic challenger to her right, and all seemed to be in vain. As 2022 began, it looked as if Zemmour would leapfrog Le Pen to the deuxième tour. However, Zemmour turned out to be an opportunity, one which a canny operator such as Marine Le Pen could exploit. War in Ukraine threw foreign policy into the limelight – Zemmour’s previous warm words for the Russian regime gave Le Pen the space to pivot to a more mainstream and, crucially, electable approach to international affairs.

Though undoubtedly a personal blow, the defection of the more extreme elements of her party, including her own niece, and more tacitly her father, lent even greater credence to Le Pen’s new moderate façade. Zemmour began to falter as his poll ratings fell, expressing increasingly radical sentiments as his credibility faded – in contrast, Le Pen appeared the sensible option.

Éric Zemmour (front) stands alongside Marine’s niece, Marion Maréchal (second from left) (Photo: Ahn de France, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The first round results would cement Le Pen’s dominance over her right-wing rivals. She took her highest ever share of the vote in the premier stage, dwarfing Zemmour’s single figure position. France’s established right wing party, Les Républicains, did so poorly, winning just 5% of the vote, that they were unable to recover their campaign costs from the state and nearly went bankrupt.

These facts went largely unnoticed by international observers, most of whom would have heard merely of Marine’s second round defeat; even then, many probably took the wrong message from the result. Yes, Macron won by a comfortable 17%, but in 2017 that margin was 34%. Le Pen’s father had been defeated twenty years earlier by 64%. Thirteen million votes is a very large number for a candidate who still, under the surface, belongs to France’s radical right tradition. If she had put in a better debate performance, that number might have been fifteen million.

Still ignored was the legislative election that followed. Le Pen’s party won a record 89 seats (up from just 8) – for the first time, they had outperformed Les Républicains and cast in stone their dominion over the right in the parliamentary as well the presidential arena. For decades the electoral system had operated to prevent this; a two-round system meant far-right candidates could win pluralities in dozens of seats but never the majority required to seize them in the second stage. Now, the cordon sanitaire had been broken. Marine Le Pen’s transformation of her party’s image from fringe jingoists to serious republicans, capable of government, was complete. The barriers to power for her had all but dissolved.

It is often argued in favour of monarchs that they make more suitable heads of state than elected presidents because they are raised with the sole purpose of being so. Marine Le Pen was the Princess of Wales of French far-right politics, who waited in her father’s shadow for the mantle to be passed. It seems that her training has served her well – she is a far better politician than Jean-Marie, and to that end has positioned herself as the true Queen of the French right, a title which in the wake of this year’s elections has become undisputed.

In 2027, Le Pen will likely stand in a presidential election without an incumbent (Macron is term-limited), with a centre-right at war with itself and a left absent its strongest voice. She is now the third most popular of all France’s politicians, behind the president and the former Prime Minister, Édouard Philippe.

Do not let the past fool you. Do not expect it to repeat itself. Marine Le Pen is ready to win.